The thing I find I’m increasingly focused on on my many lessons visits and learning walks is the gap between the general thrust of a lesson, aimed at and involving the most confident students, and the experience of students at the other end of the range. For students in, say, the lowest 20% of attainment, I think day to day school life can be pretty grim. Lessons can go on around them without them feeling that they are part of the teaching and learning flow; they are present but they are being left behind.

I’ve experienced this myself as a learner in a few contexts, most specifically in languages lessons. I’ve attempted to learn both Russian and Mandarin in classes as an adult at different times and found that I floundered very quickly. No doubt this was largely my fault – I didn’t do enough revision and practice between lessons compared to the others – but my experience of lessons once I’d fallen behind was terrible. You start to panic in the face of questions that others seem to know the answer to; you feel foolish, you start to mask your inadequacies by slightly cheating – looking things up that you’re meant to know – and you start to plan your exit strategy. For sure you do not learn Mandarin just by being in a room where other people are speaking it! If all the call and response stuff doesn’t connect to something solid, you performatively repeat the sounds in the moment – but can fail to recall the words minutes later. You can write stuff down that makes no sense to you. You can learn to ask questions but fail to understand any of the possible answers. Every lesson can feel like you’re starting again – just with a longer list of things you know you’re meant to know but don’t.

In lessons, I see students having the same experience all the time – in maths, science, geography, French, English, music, history, at every age. They are present but drifting further behind. To my mind this is a central area for focusing our efforts in raising standards and shifting the bell-curve. If we want our lower attaining students to learn more we need to focus our attention on them and teach them better, starting from where they are, not where we’d like them to be. In relation to teaching children with special needs, the phrase ‘quality first teaching’ is often used. Personally I don’t like the phrase (it gets blanded out into a wallpaper of zero action) but if you unpack it, it means what it says: don’t focus on planning catch-up interventions, focus on teaching students better first time around – especially those who are going to rely on you the most.

So – what do we do? I think these are areas to focus on:

Mindsets:

To some extent this is the area that could make the most difference because it unlocks all the rest. In every lesson, an ongoing line of enquiry in any teacher’s mind should be ‘am I building confidence with the lowest attainers?’ – with those specific students in mind. This means you need to find out how they are doing at regular points and respond accordingly. Assume nothing. It means you are never blinded by the dazzle from the top end.. you check yourself and think.. ok but what about the others. You give them time, you seek out errors, misunderstandings. You concern yourself with how things might look from the very lowest starting point and take action.

It’s also important to empathise with the mindsets of the least confident. They’re not feeling great.. unless you create the right culture, they enter the room with trepidation or resigned anticipation of not understanding much, fearing exposure, doing whatever it takes to get by but not really expecting to make progress. Culture, however, isn’t some kind of fairy dust you sprinkle via some cheesy mantras or, heaven forbid, resilience lessons .. it emerges from doing all the practical things here.

Expectations:

It’s important to get the balance right. Imagine learning the piano, starting at Grade 5. Well…that’s just not where you start is it. High expectations doesn’t mean teaching stuff that’s beyond where students are in their learning journey. It means expecting them to get to eventually get to that point and not writing them off; it means projecting a sense that it’s possible to get there. Imagine climbing a mountain with a mixed group in terms of fitness. You don’t succeed by leaving some people behind or sending them off to climb a smaller hill; you do whatever you can to get everyone up there. You vary the pace, you set sensible intermediate goals, celebrating successes on the way to the summit and, ultimately you carry people over the hardest sections when you need to, so they can at least see the view; you show them the way so they are better prepared to get there on their own another time. Keeping expectations high does not mean leaving people to flounder. You always have to take people from where they are.

Participation:

At the most basic practical level, the least confident students need to be involved – in thinking, talking, practising, puzzling things out, making connections, rehearsing. For many teachers this is an area to work on -it’s all too common for lessons to revolve around the contributions of the top third.. they do most of the talking and teachers can take their cues from a small sample of the most confident. This means the least confident students can sometimes do no talking or deep thinking at all. Practical considerations include:

- Using a strong repertoire of inclusive questioning techniques – Think Pair Share; WhiteBoards; Cold Calling – such that it is not possible to opt out or be overlooked.

- Being sure to include the least confident students in thinking – they must expect to be asked for their thoughts alongside everyone else. For the least confident this is often best done after they’ve had time to rehearse during pair talk or after providing answers on the whiteboards and when the expected answers have been solidly included in the instructional phase.

- Making sure group tasks or pair talk don’t serve as masking agents – creating spaces for students to hide behind the thinking of others. (It’s just totally unacceptable for low confidence students to end up on bubble-writing duty during a group poster task or even in a pair where the partner does all the work…)

- Including all students in reading and oral rehearsal for vocabulary development. It’s a pretty basic minimum expectation: Are you least confident students saying all the words you want them to use? One or two students knowing a word does nothing for those struggling to get their chops around those syllables. Make it normal to engage all students – yes, ALL – in practising saying new words, every time they emerge.

Crucially, participation doesn’t mean that, at odd points in the lesson, they participate – it means they participate throughout the lesson. Forget your mis-reading of trauma informed practice and culturally sensitive teaching..if you leave students out because of your anxiety about their anxiety, you’re no use to them. You’re not carrying them; you are leaving them behind.

Assumptions of prior knowledge

A big challenge for teaching is that students have different starting points. However, this is so inevitable and predictable that we ought to have some routines built around it. Before you plough into a new area of content, as part of the introduction, you have to establish what the background is with some diagnostic questioning and scene-setting.

- Curriculum Orientation: Make sure your low confidence students know where they are in the larger terrain of knowledge; take time to map it out for them. Why are we doing these questions? How does this person, book, concept, event.. link to other stuff? Make all this extremely explicit, continually reviewing the big picture so that the details make sense.

- Concrete foundations: Make learning as concrete as possible with specific examples. For example, talking nebulously about ‘the properties of Alkali Earth Metals’ or ‘the process of active transport’ can seem massively abstract; a soup of terminology. Apply all the general language and terminology to a specific set of examples – real things that students can see. Keep it as concrete as possible at all times – at every age. This applies to maths, science, geography – anything spatial, physical. Find out what students perceive when you say ‘two thirds’ or 0.35 or 6500 – what do these numbers mean to them in a concrete sense? When you say ‘juxtaposition’ or ‘anaphora’ – do they have a clue what you are on about in a real world sense? Find out.

- Language: Examine all the words you use. If you’re about to discuss the tipping point between recreational drug use and dependent drug use in PSHE, maybe take time to establish what students understand by ‘recreational’ and ‘dependent’ – otherwise they won’t have a clue what you mean. And don’t just take answers from the top end…. Similarly, if you discuss why Henry broke away from Rome… check that ‘Rome’ means more than just a city in Italy.

- Spatial or mental model: Explore the mental model you have for a concept or process and make it an explicit part of the teaching that students have time to explore theirs. This could be timelines in history, contexts for a text in literature (what was Victorian Britain like?) or imagining what particles are doing during osmosis.. there’s a diagram on the board but what does it mean? Where is all that meant to be happening?

Checking for understanding

It’s vital for lesson interactions to include everyone in such a way that the teacher is receiving information about the learning of the least confident students, responding accordingly. The important point is to check the understanding explicitly seeking out those students with partial or incorrect understanding.. that’s why you do it. You don’t just run a routine and move on, in too much of a hurry. You check expecting to reteach things depending on what your checks reveal. You have to go into the corners, asking those students whose confidence is low, and then switching things up so that you can build some confidence – explain it again, get them to practice some more, offer further examples… whatever it takes.

Five Ways to: Check for Understanding

Five Ways. A series of short posts summarising some everyday classroom practices. In Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction, he stresses the vital importance of Checking for Understanding. I explore this in some detail in this post: Check for Understanding… why…

Scaffolding

Scaffolding is arguably the central tool in this area because typically scaffolds can be pre-designed for specific areas of the curriculum and then used as an when needed. Scaffolds can take many forms:

- Sentence starters for writing or dialogue

- Partially completed examples – of writing, drawings, maths problems

- Structure guides and heuristics – (e.g. economic, social, environmental…. the three types of impact)

- Knowledge organisers – support factual writing with some facts

- Pre-made tables and graph axes… let students think about new content rather than faff with drawing tables if this slows them down to the point that they never get to the thinking part.

- Rehearsed phrases… things we say so often, everyone knows them.

I meet some teachers who pride themselves on not doing differentiation – they’ve read some cool blogs deriding this terrible idea – who then offer no support at all to any students. It’s just sink or swim. For low confidence students this is really just sink. So don’t lose the plot here…

Five Ways to: Scaffold Classroom Dialogue

Five Ways. A series of short posts summarising some everyday classroom practices. The essence of scaffolding is that students are elevated to a level of performance and thinking that they couldn’t achieve…

Time for practice and consolidation

Finally, a key concept in supporting students with low confidence is consolidation. This means you explicitly give time to bed knowledge down, to over-learn, repeat, practice, rehearse, go over it again, apply to more examples and so on. This always time well spent; everyone benefits. We have several walkthrus relevant to this including:

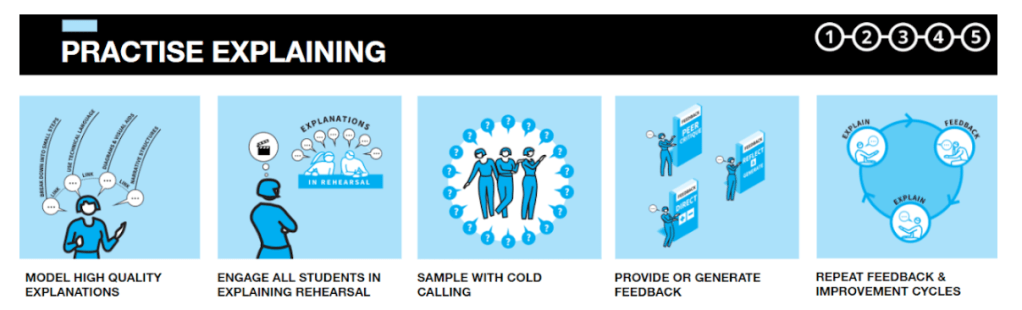

Practise explaining: You don’t know if you can explain something until you try. You don’t know if you can do it simply because you’ve heard other people do it. Practise explaining involves all students in explaining an idea to each other and then, after feedback, doing it again better.

Consolidation: This Walkthru explores multiple ways where consolidation can be achieved:

And ultimately, aiming for fluency – again, with everyone in mind.

Five Ways to: Build Fluency

Five Ways. A series of short posts summarising some everyday classroom practices. Fluency is a concept in learning that suggests recall from memory with minimal effort and a level of automaticity. Where we can do and say…

Review and Reflect:

So the question now is this: What’s it like to be at the lower end of the attainment range in your lessons? What are you doing explicitly that supports those students to grow in confidence.? How are you making sure you are taking them with you and not leaving them behind?

[…] ‘If you leave students out because of your anxiety about their anxiety, you’re no use to them. Y… (Tom Sherrington) […]

LikeLike