I’ve written several blogs about Think Pair Share in the past, because I think it’s such an important teaching routine for teachers to master:

The ‘Washing Hands’ of Learning: Think Pair Share

A blog about something really obvious but worth spelling out. After 25 years of teaching, I’ve been through a fair amount of dodgy INSET/CPD. As a result I am…

Think, Pair, Share Forensics.

Think Pair Share is a powerful and important technique that should probably play a key role in every teacher’s repertoire. It’s the key to giving every student the opportunity…

However, doing this well isn’t massively challenging but it does require some thought. During my many lesson observations, I frequently listen in to hear what students are actually saying after they’ve been set off to talk to their partners and, to be honest, I often feel that with a few tweaks to the routine, they’d have done a lot better. Quite often an excellent question with rich discussion is there for the taking but the teacher then uses the all-too-common short-cut: ‘OK everyone, have a chat on your tables.. what do you think about X?‘. And that’s the instruction.

But ‘have a chat about X’, despite its ubiquity, is just not a reliably good basis for paired discussion that supports all students to think, to speak, to rehearse and to learn more. Teachers can’t listen to every set of pairs talking at once so, unless they set it up well in advance, students can exchange all kinds of silliness and shallowness without the teacher noticing.

I’ve encountered some fabulous questions recently, all of which had great potential and generated some superb responses:

- Think of reasons for and against the idea of charging people to climb Snowdon (in response to overcrowding at weekends). Express your answer as ‘on the one hand.. but on the other hand…. (KS2)

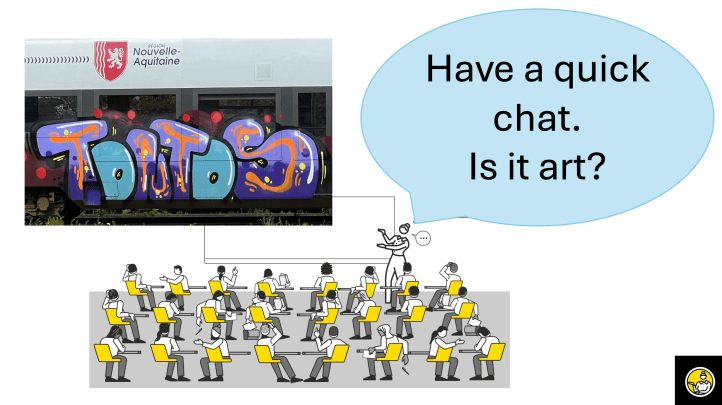

- Looking at the sample of graffiti photos, decide whether they are art or vandalism. Give your reasons. (KS3)

- What are the various associations you make with vampires in films and literature? Explain the connection to the concept of ‘Gothic’. (KS3)

- What words might you use to describe the central character? Think of three each, share them and decide the best ones. (KS1)

- What are the key social factors that lead young people from recreational drug use into dependent drug use? (KS4)

- Looking at the sets of reactants, decide on your tables, which will lead to a reaction happening and which ones won’t, giving your reasons. (needing knowledge of reactivity series) (KS4)

- What were the there types of consequences of the earthquake? Give an example of each. (aiming at social, environmental and economic) (KS3)

However, despite the promise, here are some problems I’ve witnessed, using these questions as examples. Each of these was a real situation but I’ve deliberately mixed up contexts and scenarios with the subject matter so they don’t relate to individual teachers.

In each case, some students gave great answers. But… not everyone….

Problem 1: Not structured for full participation

In the Vampire question, two girls immediately turned back to talk to the two behind them. One of them said.. ‘………Blood..? ‘. The others said ‘yeah…. . Cool’. End. That was it. They waited until it was over; the teacher called on one of them to share. The chosen girl repeated ‘Blood’. The teacher said ‘excellent’ and she moved on. It wasn’t excellent. Only one student out of four did any thinking or speaking. It was a shallow response that most hadn’t even contributed to. The teacher didn’t notice because she was busy on the other side of the room.

In the equations question, the instruction was ‘on your tables… ‘. One table in front of me had six students. A boy turned to the others, smashed out all the answers correctly , not pausing to ask anyone else. They just bowed to his confident knowledge and nodded, happy that their table had the answers. Only one out of six, the dominating boy, said things like ‘aluminium is more reactive than iron’ out loud.

In the ‘describe the central character’ question, several pairs of children turned to each other and simultaneously yelled adjectives at each other. Not a lot of listening was going on! The teacher did stop to redirect -but that was after quite a time when it was just paired yelling.

Problem 2: Insufficient knowledge or scaffolds for access

Here, you find students just don’t know how to organise their thinking or they are expected to remember quite a lot of facts as well as organise their argument and it overwhelms them. In several of these questions, where it went wrong, students couldn’t formulate responses because they didn’t have the knowledge at their finger tips in the discussion.

In the drugs question the boys next to me simply didn’t know what everyone else was talking about. I offered help. It turned out they didn’t know what recreational or dependent meant. Once I’d converted this to ‘drugs for fun’ and ‘feeling you can’t live happily without drugs’ – they were away. But that initial block was real for them even though nearly every other pair seemed to be fine.

In the graffiti question, one set of boys were just trading opposing answers like it was City vs United. Vandalism. No Art. No – it’s vandalism. No it’s not, it’s art. No argument, no justification, just repeated assertion of their choice. They just didn’t know how to frame their response; they didn’t have models to work from. They were busking it without enough knowledge to think with or worked example to prompt them or to use as a scaffold. When I spoke to them they could actually give reasons but in their talk, this didn’t surface.

The same happened for some students in many of the other situations. You can’t just guess your way to a reasoned argument.

Problem 3: Not structured for depth.

In the earthquake question, some responses were one thing like ‘buildings fell’ or ‘water supply problems’ or ‘roads all cracked up’. In the same room, other students were saying ‘Economic impacts included..; social impacts included… ; environmental impact included…‘ They knew their stuff! They also thought to give an extended answer using the heuristic they’d learned. The problem was that this wasn’t explicit. Students were able to stop at one idea and wait to share it.

In the ‘describe the character’ question, one sweet pair turned to each other and one whispered ‘let’s use adjectives‘. They’d misunderstood the question – which was meant to generate a list of actual adjectives. If the teacher had asked them to think of say three different adjectives each, then share and compare, then they’d have known what to do can could have given a good answer.

This ‘one answer is enough’ issue is so common. It was the same in the vampire question – not only did the teacher allow only one student to think; she also accepted a one word answer. There was no attempt to specify, for example, at least three ideas.

So, as described above – ‘have a quick chat in your pair/at your table’ just doesn’t go far enough. However, rather than suggest that, therefore, pair talk is all a bit messy and therefore should be avoided, I would argue that it’s just too important to get wrong – and it’s really relatively easy to get right. To make pair talk work really well, you just need routines that are that bit more rigorous. I think there are three golden rules:

- Ensure every student speaks and listens

- Ensure all students can access the knowledge to think with.

- Structure the question to scaffold for access and depth

Ensure every student speaks and listens: Firstly, it’s pairs, not tables. Just make the commitment to establish pairs and don’t think ‘tables’ will automatically run a fully inclusive conversation – they won’t. Then, make it your habit – and therefore the student’s habit – that ‘pair talk’ means: everyone thinks on their own; then person A shares there ideas; then person B shares there ideas; then they combine to form an agreed response. You are absolutely explicit about the turn taking, the listening and the pooling of ideas. This way everyone speaks and listens. It’s not hard – you just need to establish the routine and follow it through. Supervise/monitor the class at an overview level to check every single student in involved before you try to support anyone.

Ensure all students can access the knowledge to think with. Check for understanding of key terms in the question and give students resources to refer to during the discussion so that they can inform their discussions. This could be phrases to use; facts and quotes; exemplars. Do they have a diagram, a photo, the text, a table – something that gives them the tools they need to work with to inform their thinking? Get them talking about a tangible set of information or a stimulus that is there in front of them rather than imagining something or just dredging up their tenuous or possibly incomplete knowledge.

Structure the question to scaffold for access and depth: Set the question so that the answer must be given in a certain format – at least to begin with. For example:

- –> give three adjectives; three reasons; one advantage and one disadvantage

- –> use the format: On one hand ________ but on the other hand __________

- –> this example is a piece of art because of ____, _____ and _____ whereas this example is vandalism because _______, _______ and _________.

- –> reaction A will happen because __________. but reaction B can’t happen because.______

Or demand that answers are inherently extended because your question is to provide a full explanation of a scenario or event or problem as if to someone else, in as much detail as is necessary. This can’t be done in a short reply – you expect multiple steps to be articulated.

With those three golden rules in your mind, pair talk is completely inclusive, scaffolded to the extent needed and builds on and develops solid, deep knowledge rather than on flimsy knowledge.

If you do find yourself saying ‘ok guys, have a quick chat on your tables about X…. Go’.. just listen in closely to what is actually being said… you might be in for a surprise! If it’s not great, you can reset the task and do it more rigorously. But it pays to set things off well in the first place and to make this your habit

Very helpful as we head into a new term and I’m encouraging fewer ‘hands up’ and more cold calling after paired talk.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, this is a great reminder of what and why to do chat, as well as the how.

Stephen Thomas | KS3 Teacher

Central RSA Academies Trust Ipsley CE RSA Academy – Winyates Way, Winyates, Redditch, Worcestershire B98 0UB tel: 01527 525725 | fax: 01527 523457 web: http://www.ipsleyacademy.co.ukhttp://www.ipsleyacademy.co.uk/

Ipsley CE RSA Academy, an academy operated by Central RSA Academies Trust, a charitable company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales – Company Number 08166526 Registered Office: Suite B06, Assay Offices, 141 Newhall Street, Birmingham B3 1SF

[https://www.centralrsaacademies.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/08/all_schools_sig-1.png] ________________________________

LikeLiked by 1 person