In December, Efrat Furst delivered a superb masterclass as part of our In Action series where she explained the stages of learning using the models used in her brilliant blog posts such as https://sites.google.com/view/efratfurst/understanding-understanding. Within the context of her model, Efrat made a distinction between rehearsal and retrieval practice that resonated strongly with what I see in lessons. I think it’s a crucial thing for teachers to understand and act on.

As I understand it, essentially, the first stages of learning a new concept involve creating a set of connections that allow us to make meaning from the elements that make up the concept, linking them together and binding them to knowledge we already have. Forming these connections requires some short-term rehearsal, establishing a unit of knowledge that is stable and coherent enough that we can later retrieve it. If we don’t establish a basic level of stability and coherence, there is nothing secure enough for us to retrieve.

This makes a lot of sense to me and it’s something I see in lessons very often: students are being asked to recall knowledge through retrieval practice activities when actually they had not engaged in sufficient discrete rehearsal of the embryonic knowledge in the first place. Let me give some examples:

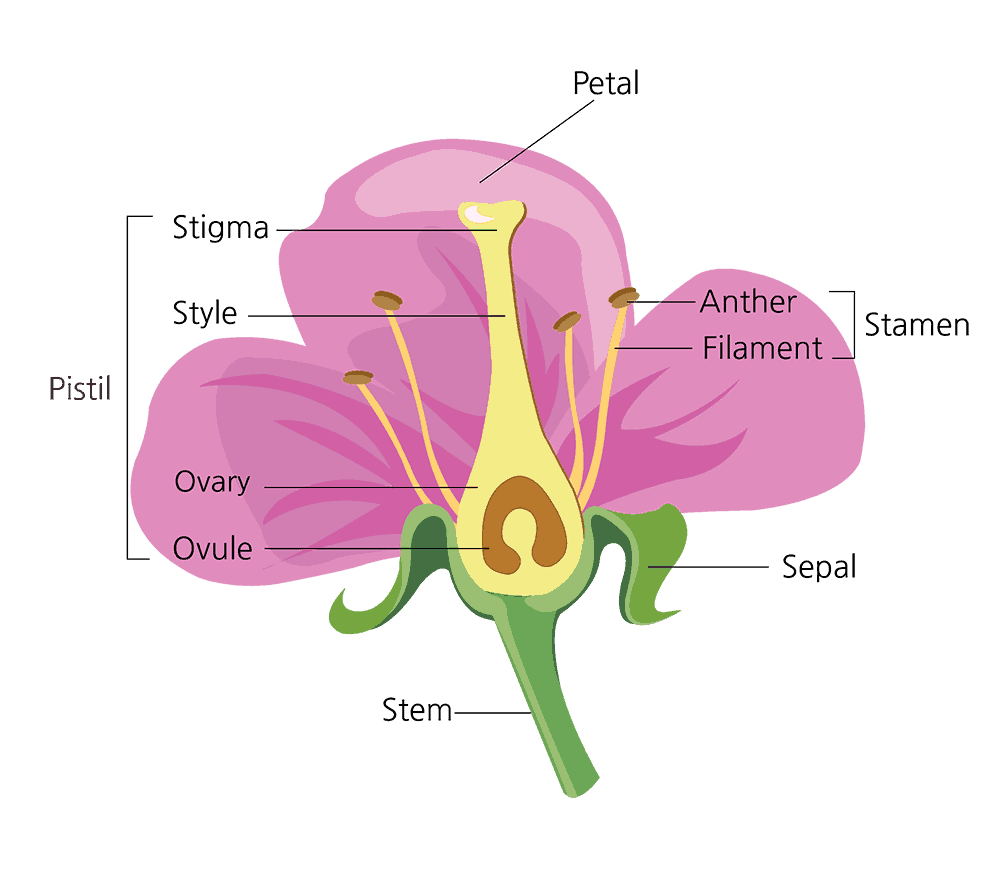

Stamen: anther and filament

To establish understanding of ‘stamen’, we need to connect the word to something meaningful: we link the sounds and spelling of ‘stamen’ to the concrete object – or a set of them – that we have observed ie the bits in a flower with pollen on them. We link it to the sub-components filament (the long thin stalks) and anther (the bits on the end that actually have pollen on them) – and also pollen. Making these connections requires rehearsal, linking images to words with a structure: each stamen is made up of a filament with an anther at the end; the anther carries the pollen. Anyone who can later retrieve this knowledge will need to have formed it in the first place – at least tentatively.

What might rehearsal in this context look like? There are lots possibilities:

- annotating an unlabelled diagram and a photograph from a list of given words – helping to link the written form of the terms to their physical reality.

- explaining to a partner, talking through what each part of a flower is called and what it does

- answering some questions where an expected answer might be: the anthers are parts of a stamen that carry the pollen; the filaments are the part of the stamen that holds up the anthers – said verbally, not just in writing.

Crucially – and this is where lessons can go wrong – if you want every student to know these facts, they all need to have time to rehearse them as part of the learning. They all need to say the words stamen, anther and filament; they all need to rehearse linking the structure to pollen and to an example flower, they all need to connect real flower part examples to the words that describe them.

Then, later, you can engage students in retrieval practice where they try to retrieve the knowledge element in response to a stimulus of some kind. This might be 20 minutes later or 20 days later.. Doing this strengthens the knowledge itself and the pathways that allow it to be retrieved, building up to fluent recall with practice – ie when you just know that those things in the flower are stamens made up of filaments and anthers, every time, effortlessly. Crucially – students who do not get the chance to successfully rehearse those initial connections (for example, never saying the words or having to do more than stick a labelled diagram in their books) – are highly unlikely to be have much success with remembering them later. (This links well to Nuthall’s ‘rule of three’).

avec mes amis

With languages this plays out all the time. We can’t remember phrases unless we’ve been able to say them successfully before. This requires deliberate rehearsal, building up chunks of language that we can then remember and use in response to a stimulus. For example, in this sentence there are three chunks:

- Je suis allé /au parc/ avec mes amis

- I went/ to the park/ with my friends.

Each one of them warrants rehearsal. avec mes amis – which sounds like avek maysamee – can be rehearsed on its own. With my friends = Avec mes amis. This rehearsal doesn’t have to take long but it pays to give everyone a chance to get their tongues around it a few times. Similarly with au parc (it’s not a la parc.. it’s au parc) and Je suis allé… ( we say je sweezallay for I went). Each little nugget of knowledge has to form and have meaning and then we can practise linking the nuggets together with others:

- Je suis allé /au cinéma /avec mes parents

- I went to the cinema with my parents.

We can’t produce these phrases with any kind of fluency or confidence if we haven’t first rehearsed them. However, once we have a repertoire of learned chunks, we can start retrieving in response to questions, linking up a set of chunks that have meaning and coherence in themselves – so much easier to remember only three chunks than 8 words:

Qu-est ce que tu as fait le weekend dernier? Je suis allé au parc avec mes amis

Where I see students flounder in MFL lessons, it’s very often the case that their success at the rehearsal phase is poor – they’ve hardly had the chance to practise saying each chunk and now they’re expected to be messing with all kinds of variations. There’s not enough repetition. Sometimes the teacher only gets a sample of students to verbalise the phrases or they’re too concerned with students ‘getting them down in their books’. I’ve met too many students with full-looking books of phrases they can’t say with any confidence; every lesson adds to the list of things they can’t say rather than builds their repertoire of things they can say.

In general, this idea applies to all language – as explored in this post:

Building Word Confidence: Everyone read, say, understand, use, practise.

A very common phenomenon in many lessons is that students encounter new words. The way we approach this ought to be something teachers think about explicitly so that effective strategies are used. I’ve seen explicit vocabulary…

However it also applies to any set of knowledge that features in retrieval activities.

Density:

If you are expecting students to remember that density = mass/volume and to explain why a light iron nail sinks when a giant heavy log of wood floats they will need time to rehearse that thinking at the point of learning it. Density has to mean something tangible; students need a mini schema for density that helps them distinguish it from mass – the idea that a heavy object can be less dense than a light object. Students need an opportunity to mull this over, formulate that mental image and explain it to themselves or to someone else to check they have grasped the meaning. This might be supported by images, a practical demonstration, a hands-on practical with blocks of the same size but different materials and masses, using the equation and getting the units of grams per centimetre cubed straight in their heads.

And finally, a firm favourite –

Henry VIII’s Wives.

How not to misfire.. exploring the learning process with Henry VIII

Having written about lessons that mis-fire, I was asked to suggest what people should do instead. That’s a mighty big task because, what you might do depends on what exactly you want students…

Within the wider narrative of Henry and his six wives, there are numerous elements of knowledge that warrant rehearsal. One that I have encountered is the concept of ‘Rome’. When asked, ‘Why did Henry want to break away from Rome?’ – the concept that Rome is the power base for the Catholic Church is vital – as is the idea that Britain was a Catholic country until 1533 when Henry broke away and could then marry Anne Boleyn. Students need time to rehearse these ideas: the link between Rome as a city, the Catholic church (as distinct from being Protestant or Church of England), the Pope, rules around divorce..each little nugget has to have meaning and then make sense as part of a wider framework. I’ve met students where these elements had never been rehearsed fully so they didn’t ever get what Rome had to do with an English King or that Catholics and Protestants are all Christians.. And here they were doing a retrieval practice quiz as if it was just a case of remembering things they once knew.

So that’s the message: teachers need to make sure they get all students doing plenty of mental and verbal rehearsal and then, once they’ve been successful in forming connections, worry about retrieval practice later on to make sure students are strengthening those connections and building some fluency with their knowledge. In practice I think this requires a lot more emphasis on pair talk with students talking things through, practising explaining, explicitly using new vocabulary, and on the range of generative learning activities such as mapping, self quizzing, drawing and imagining – all within a rehearsal phase that involves every student.

Note: The concepts explained by Efrat Furst feature in WalkThrus Volume 3.

See Also:

When daily quiz regimes become lethal mutations of retrieval practice.

One of the most common areas of development in schools over the last few years has been in the area of retrieval practice – supporting students to remember what they’ve been taught, gradually, steadily deepening and extending their schema for the material in hand, building fluency and confidence. However, whilst there has been a lot…

If we look at either Atkinson & Shiffrin or Baddeley & Hitch, both models emphasise rehearsal in STM/WM followed by storage in LTM and retrieval from LTM. This isn’t new but dates back to 1968 and 1974. But it’s important so thanks!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nothing new at all. Thanks Paul

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely important, and I would add to first embed, such as in a worked example, so: embed, rehearse, retrieve. Jumping to a fun quiz online game without presentation and guided practice of examples and non-examples – followed by the ample rehearsal opportunities you mention – is a sure fire way to eliminate the effectiveness of retrieval.

LikeLike

[…] here’s an interesting piece on rehearsal and retrieval from Tom Sherrington “Rehearsal first; retrieval practice later […]

LikeLike

Mr Gradgrind would be so proud. This isn’t teaching, it’s programming. Shame on you all.

LikeLike

Haha. I suspect you might not fully understand how learning happens then. It’s not all Dead Poet’s Society. Without very solid, secure, technical instruction too many children fail to grasp basic ideas.. and teachers understand that.

LikeLike

[…] Sherrington expertly explains why sufficient rehearsal, particularly in the form of verbal practice, is necessary before engaging […]

LikeLike

[…] this blog post Tom Sherrington distinguishes between rehearsal and retrieval, noting that teachers need to ensure […]

LikeLike

Awesome article, thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person