The RSA Pinball Kids Initiative.

There has been a lot of discussion in recent weeks about exclusions from schools with a string of newspaper articles exploring the theme:

- The news of rising fixed-term and permanent exclusions is covered by The Guardian here. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/jul/19/sharp-rise-in-pupil-exclusions-from-english-state-schools

- This report describes some responses – the ‘Wild West system of exclusion is failing pupils’, say MPs. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/jul/25/children-abandoned-after-school-exclusions-say-mps

- Tom Bennett comments here about the rise, suggesting zero-tolerance policies are not to blame: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jul/26/school-exclusions-zero-tolerance-policies-disruptive-pupils.

- The Guardian made a story from some high rates of exclusion from specific schools: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/aug/31/dozens-of-secondary-schools-exclude-at-least-20-of-pupils

- This week the organisation PTE published an open letter supported by a range of school leaders, teachers and commentators defending the exclusion process (if I was still a Head I’d have added my name). https://www.tes.com/news/curriculum-campaigners-defend-exclusions

As ever, there’s a sense of polarised camps forming on twitter, either pro-exclusion or anti-exclusion, each exasperated by the other; each claiming the moral high ground. I’ve expressed some clear views myself – it can be an emotive issue and I don’t take too well to being preached to on inclusion by people who haven’t had to manage super complex institutions serving areas with massive social care needs and chronic deprivation and where the safety of children, teachers and the wider community is at stake every day, let alone the learning in classrooms.

However, I do also recognise that, as ever, the reality is complex, context dependent and deserves to be discussed without polemics. I’ve been involved in two events in the last week that have modelled this approach. The first was the launch of an excellent initiative by the RSA- a research programme looking at exclusions and provision for students at risk: The Pinball Kids. This follows from the superb publication of RSA’s The Ideal School Exhibition written by Director Julian Astle.

I was invited to participate in the roundtable event at RSA’s HQ with 20 or so others, largely because the initiative takes its name from a blog I wrote introducing the idea of Pinball Kids: No Excuses and the Pinball Kids. It’s about students from whom sanctions-driven ‘no excuses’ approaches don’t work; students who hit the boundaries all week long despite the consequences. I was invited to set the scene by sharing my experience as a Headteacher struggling (and not succeeding) to balance intense competing pressures: the need for schools to be safe, for teachers to feel safe and supported, for parents to have confidence that bullying is tackled – and for each individual child’s needs to be met within the limits of the resources available both in the school and in the local community.

The second event was a day of training with Tom Bennett, supporting him in delivering a follow-up ‘booster day’ for school leaders enrolled on the Tom Bennett Training programme based on ‘Creating a Culture‘, the report Tom’s independent review body produced in March 2017. The whole day was focused on creating and maintaining a positive behaviour culture: nobody mentioned exclusions at any point in the day; it was all about what you do before you reach that point. Most of the challenge is to give a consistent message; to create a coherent ethos that all teachers support in their actions as well as their words. Sanctions are the backstop but the message of love, ambition and mutual respect has to be at the forefront. Culture + System. Inseparable. (See also this post about The Hive Switch at Turton High School. Principles over patch-ups)

Between these two events there’s a model for finding the answers: superb training and excellent dialogue between professionals at the sharp end.

Context and Reality Checks.

One of the issues I find is that people approach the discussion from very different perspectives and I’m certain that lots of commentators don’t really understand just how challenging behaviour management can be or just how limited the options are in a given context. Very often people confused fixed term and permanent exclusion in the discourse and, of course, there is a wide gulf between exclusions for ‘wrong colour piping on the blazer’, ‘persistent disruption to learning’ and ‘violent and intimidating behaviour’.

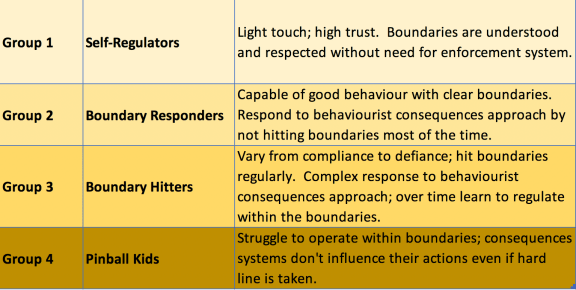

I have a mental model that puts students into four groups:

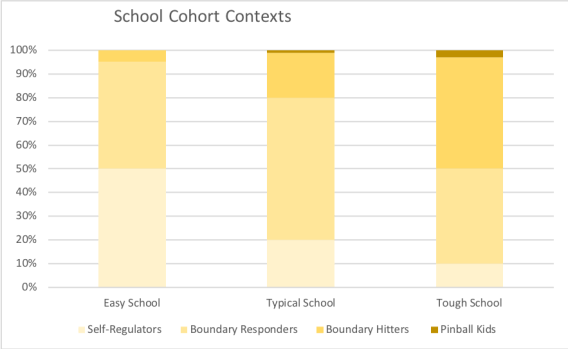

The numbers of students in these groups varies massively from school to school – often a function of social care issues rather than the crude deprivation indicator of Free School Meals or Pupil Premium -ie similar PP levels don’t equate to similar contexts; not even close.

In some (Easy) schools, simple rules with light tough enforcement are totally sufficient. You hardly need detentions, never mind exclusions.

In a more typical school the majority of students need and respond well to a clearly communicated and well-enforced behaviour system. Usually, in order to succeed, it’s important for everyone to know that there is a bottom line. The Group 3 students may receive occasional fixed term exclusions – either as a straight consequence for a specific action or a last resort after an accumulation – but this has a big impact on the all the other students too: they know that the boundaries are real and they modify their behaviour. Schools need to attend to the needs of the majority whilst always having concern for those at the fringe. Behaviourist approaches are highly successful for most children in the context of schools with a warm, friendly and supportive culture and clear boundaries where habits for happy coexistence and effective learning develop and are maintained.

In a tough school, the Group 3 cohort is much bigger. Here, you might have students who not only find it a challenge to sustain the behaviours required for learning in a shared space but also sometimes present a threat to others: staff, students and themselves. The scale of numbers means you might not have resources in school to provide secure internal provision that allows all at-risk students to be taught alongside others in appropriate groupings with the right level of safety. If a student assaults another pupil or intimidates a teacher, or brings a knife or sell drugs, as well as giving a message about how unacceptable that is, on a purely practical level you need somewhere for them to go to create space between people prior to a repair process or a disciplinary process. That’s not always easy if you’re dealing with several students in crisis on one day and it can massively backfire if the message given is too weak – that certain behaviours are tolerated way past the point of safety.

Mixed into this already complex situation are the 4th group, the Pinball Kids. These children have chronic issues with self-esteem, self-regulation, dealing with authority, resolving conflict….. the list goes on. Here, sanctions being given or not has little impact on their behaviour: they’re too emotional; too hardened or lack the capacity to conform to the social norms required for collective activity unless all their needs and concerns are met immediately. Exclusions are like water off a duck’s back – they have no impact on behaviour. Even a very tough school might only have 20 students like this – a handful in each year group – but that is enough to drain resources to zero on a daily basis. The challenge of keeping these children in mainstream education without causing unacceptable damage to the learning or well-being of others is massive.

The Pinball Kids conversation covers what schools can do alongside what else needs to be available in a community in order for schools to succeed in their complex task. Alternative Provision is sorely under-funded and in some areas is dire or absent. In other areas the PRUs that exist are excellent; they are the places where the specialists needed can be found. Permanent Exclusion leading to a PRU place does not have to be viewed as a disaster. At KS3, that’s much harder to argue – because it’s rare for children to come back. The RSA research will explore this issue.

There are obviously other mechanisms like managed moves between schools: some schools have good networks and can move students around instead of excluding them permanently. (Personally I think moralising about exclusions whilst doing managed moves is rather thin ice – they’re different but not that different). However, there are contexts where the scope for adopting this approach has major limitations – either due to geography, housing, MAT/LA structures, capacity in schools in general. I’ve dealt with several managed moves but it’s always a case of give and take. Sadly, there are too many takers and not enough givers in this situation. I hope this will also be something the RSA looks at. It should be universally true that schools play a role in the safety net of provision. I can’t bear the ‘take it or leave it’ approach that some schools project – the idea that, if you don’t like it here, you can go to the softer school down the road. This serial kicking the can down the road is unacceptable. All schools serve communities or at least they should and that should entail shouldering some collective responsibilities. Shouldn’t it?

Finally, there is the problem of conflating the complex issue of school exclusions with off-rolling. I know of a newly (forcefully) converted academy that has apparently lost over 70 students from KS4 in a year through off-rolling. Presumably other schools in the area have had to absorb them. It could be that this wave of hard-line enforcement will pay off – transform the school. It could also be that other approaches would have worked or that some of those 70 students are victims of gross injustice, covertly expelled without due process. We don’t know. My view is that it would be wrong to judge unless you knew precise circumstances case by case. A high number could indicate the extreme scale of the challenge a school faces; it could be that, in the big schemes of things, an early wave of hard-line action is absolutely what is needed to engineer radical change so that, long-term, more children receive a better education: they feel safe, their teachers stick around, disruption and bullying no longer happen.

I’d suggest it’s wise to listen to people on the frontline rather than assuming they’re doing it wrong for their precise context – especially if they succeed in creating a great school. That said, it might be interesting to see if school’s behaved differently if you had to provide tracked evidence of destinations for all students that leave school after Year 9 and even take responsibility for their outcomes .

So my main message is: don’t judge; talk. Don’t project from one context to another because they’re all different. Ask yourself – how do I know for sure that I’d manage that differently? Share ideas and do your bit in the system. If you want to help I strongly recommend getting in touch with Laura Partridge at the RSA to share your thoughts. (Laura.Partridge@rsa.org.uk ). They are looking for good policy recommendations informed from views across the sector.

Much to agree with and several points I would challenge. Another time maybe as, sadly, I’m losing patience with polarised debate (often ill informed). However, one point you make Tom gets my temperature soaring (and, I’m sure that’s not your intention);

“Permanent Exclusion leading to a PRU place does not have to be viewed as a disaster. At KS3, that’s much harder to argue – because it’s rare for children to come back.”

P.ex IS a disaster and does not need to happen where referral systems and intervention between PRU/AP and mainstream are properly structured. The notion that Pex leads to PRU is one that needs eradicating since, as you point out, return from Pex is rare.In addition, Pex sits with a YP for years and csuses sometimes irreparable damage. There are LAs however where transition between PRU/AP and mainstream and Special schools are smooth reducing Pex to almost nil.

Whether a school employs behaviourism, nurture, restorative, reward/sanction, internal exclusion, etc is not the biggest barrier to smooth transition and effective collaborative processes. The issue is lack of legislation which secures the childs educational rights in a humane manner (not at the expense of other children or staff I should clarify). Enforcing schools accountability for the child irrespective of the provision in place would answer most if not all concerns.

PRUs should be conduits and safety valves affording YP access to specialist support and assessment awaiting transition through EHCP, reintegration or managed move whilst providing continuity of education. It also therefore enables schools to manage without resorting to exclusion for spurious reasons; improves professional regard, suport and good practice sharing; strengthens the wraparound approach to supporting YP. These benefits are not an exhaustive list either.

I hope your call for a more respectful and informed dialogue gains traction but won’t hold my breath as yet.

Kind regards sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good comment. I think PEx can be a disaster but I’ve known it not to be – especially when strong signal needed to be sent. Even PRU recommended PEx as quickest and best way and best message. Fluid interchange is the goal – but wow it can be so clunky and some AP is desperate – bordering on being ‘crime school’. Big issue, horribly neglected with focus on blaming schools.

LikeLike

A very good article which promotes a mature debate, which is all too often lacking in this area, especially by sound bite-grabbing newspaper headlines. However, making schools accountable for students that they have no influence over raises a number of issues: as a Curriculum Leader in a inner city academy we already have a number of cards stacked against us. In reality, we are already responsible for a number of students that we rarely actually see in the classroom for one reason or another, and when the achievement data for these students is mixed in with the general data it gives a very skewed picture of the very good quality education that we provide for the vast majority of students sat in front of us in the classroom on a daily basis. At least let us be judged on the data for the students that we actually teach and give us a fighting chance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Solutions and reality checks in the exclusion/inclusion debate. #pinballkids […]

LikeLike