I’m coming back to blogging after a big hiatus and finding several times that an idea for a blog post has struck me – only to find I’d written about it already! Teaching issues don’t change much. However, one thought I’ve been having recently is about how vague people can be about their ideas, their intentions, their sense that things need to be better, their desire for other people to change their behaviours. All this vagueness leads to inaction, confusion and a lot dissipated energy; teachers and leaders can be busy without moving forward.

To some folk, the very idea of precision in educational settings seems misplaced – after all classrooms and big organisations comprised of humans are complex and turbulent places. To many, teaching is all art, not science; it defies measurement. Precision is surely unattainable – pointless even.

Earlier this week, I posted my annual April Walkthrus update… hilarious right!?

I’m not sure whether I’m poking fun more at people who read spurious precision into research data or quote percentages of teacher gradings to decimal places or create checklists of non-negotiables – or the people who immediately presume this is what is meant whenever the word ‘precision’ is used in an educational context.

People are often keen to protect their individuality, their autonomy – they prize it highly and react against anything that threatens that. Precision appears like such a threat. But I don’t see it like that. Precision isn’t (I mean very obviously isn’t) about micro-managed behaviours and spurious measures; really it just means the opposite of being vague or hoping people understand; it means providing clarity and guidance so that people know what things mean and what they’re meant to do. My sense is that, in the absence of well defined guide rails of some kind, the beliefs and behaviours of groups of teachers and students will always, always diverge – often rapidly and significantly. You never need to worry about definitions and guidelines constraining people – because they only ever serve as a framework within which people then express themselves in all kinds of ways.

However, if you don’t begin with ideas and routines that are sufficiently precise, people don’t know what to do or they all pull in different directions or, very commonly, they don’t do anything different at all; you just get in inertia and stagnation – not because people don’t want to change but because they think they’ve already doing whatever is that needs to be done.

In my work with schools, a common issue that holds people back is a lack of precision:

- precision in how team meetings might work so everyone participates

- precision in what specific teaching techniques entail

- precision in how a coaching or PD operates within the timetable and calendar

- precision in how agreed actions are followed up or recorded

- precision in how we understand feedback and the best way to generate it

- precision in defining expectations of students and of adults in a group.

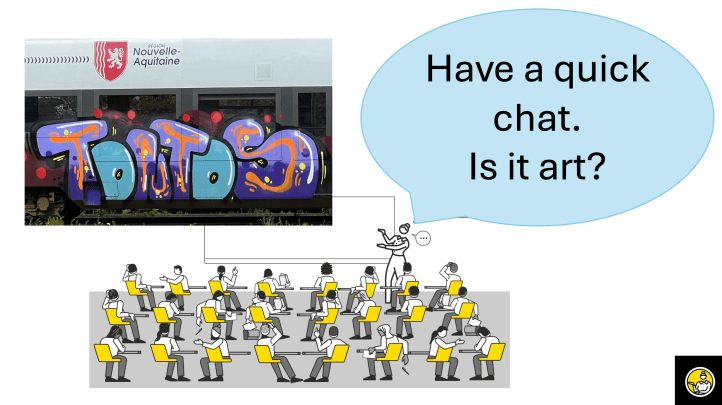

A lack of precision in defining Think Pair Share can lead to lots of very poor ‘have a quick chat’ turn and talks. If even one or more children don’t actually have a chance to think, talk and share – , then it’s not precise enough to be of value for every child. This kind of thing matters. For me – and I know, I would say this – there are almost no concepts in teaching (differentiation, cold calling, modelling, show-me boards, modelling, metacognition) that communicate their meaning in a coherent replicable manner in the absence of strong codification. Hence Walkthrus. Obviously! You need to spell things out – otherwise people invent their own version and we talk at cross-purpose. This isn’t specific to certain words or concepts (people are always down on differentiation, for example) – it’s true of all words and concepts. Be precise!

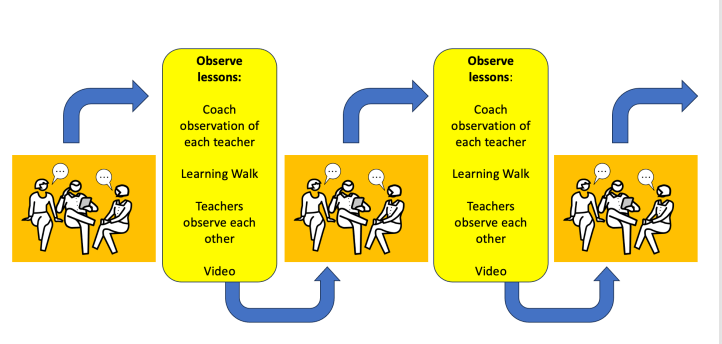

A lack of precision in defining how a cycle of training, planning, observation, feedback and improvement might work means that key elements often don’t happen. For example:

- we are always popping in and out of each other’s lessons: Are you – really? Is that the best way to support a teacher’s improvement? Even if you pop in, what happens next?

- I encourage my team to visit each other whenever they can: But do they do it? Do they have time? All of them? – how often and what difference does it make?

- we have lots of informal chats about our lessons: Sounds nice but is that how people improve? Is everyone having these chats?

- we have a great open door policy; people are always welcome to come and see me teach. Nice – but how often does that happen and so what if they do? Do they teach better?

This stuff is all lovely – all fuelled by good intentions – but it’s not remotely systematic enough, not precise enough – to be relied on to drive a whole staff of people on and improve teaching in any significant way. A PD system is too important to be left to goodwill and good intentions; it needs to be planned, embedded, built-in, taking account of people’s time and made to happen as part of their routine work, not hoped for as a bonus extra.

Finally, precision in a coaching process is often lacking. This can lead to teachers being ‘given feedback’, ‘held to account’ – and all that- without ever being asked what they think about their decisions, their situation awareness, their personal priorities and beliefs. Meetings or group coaching sessions can be run such that they don’t involve every individual person sharing ideas and end up being a talking shop, not a serious action planning session leading to commitments to change over a short period, prior to the next review; each meeting happens as if the last one hadn’t.

If you want strong coaching – whether one-to-one, in pairs or in teams (all equally powerful in different ways) you need a precise protocol for how to run the discussion to maximise their impact and to make sure everyone knows what they are doing. The Bambrick-Santoyo 5Ps (praise, probe, problem, practise ,plan) model is just superb: a nice precise structure for a superb coaching conversation. Everyone can learn how to use it – and here’s the key bit – SO THAT teachers can ALL talk and talk openly about their issues and plan solutions to their problems in a guided, collaborative fashion – such that they’re committed to change in their practice.

So – if you baulk at the idea of precision, ask yourself why – and what your alternative is. Adding clarity to how we talk about teaching, how we define our system and how we run our coaching sessions can only help. It never ties people down – people are too naturally divergent for that to ever be the issue.

End Note: Increasingly I do not regard ‘coaching’ to mean the one-to-one scenario. Partly because this so rare to find across the system (ie where every teacher has a coach), so I’m not especially interested in it, but mainly because paired, small group and team coaching are not only more common but also often the true drivers of change – it’s where the action is so I choose to define coaching as the dialogic process, not a particular configuration of individuals.

I’m so glad you’re back Tom! I’ve missed your thoughts and really enjoyed reading this. As someone who has led coaching in my school I agree with everything you say here.

Best

Nicole

Sent from Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef

LikeLike

Thanks Nicole. Good to be back.

LikeLike