At ResearchEd in Cape Town I presented a workshop exploring two relatively recent reports from the Education Endowment Foundation – the 2018 guidance report Metacognition and Self-regulated Learning, and the 2019 report Changing Mindsets: Effectiveness Trial.

Essentially, my argument is that these papers support the view – one that makes sense to me – that schools are better off investing time and energy in adopting strategies that develop metacognition than those focused on growth mindset interventions. I’ve made this case via different posts including the following:

School walls are oozing with unhelpful growth mindset cheese…. – where I suggest that the generic messaging that is all too common, isn’t helpful. Telling students not to worry or give up or that you can’t add fractions yet! – doesn’t do enough to help them add those fractions.

Engineering Success. A positive alternative to generic mindset messaging – where I suggest that we should focus on the specific learning steps needed for students to succeed, setting aspirational goals but focusing on achievable next steps within the details of a subject, rather than nebulous mindset messaging.

The EEF Mindset report is about one detailed RCT where students received several sessions teaching them about mindsets and teachers also received training. Here are some excerpts:

Key conclusions

- Pupils in schools that received the intervention did not make any additional progress in literacy nor numeracy—as measured by the national Key Stage 2 tests in reading, grammar, punctuation, and spelling (GPS), and maths—compared to pupils in the control group. This finding has high security.

- This evaluation also examined four measures of non-cognitive skills: intrinsic value, self-efficacy, test anxiety, and self- regulation. The evaluation did not find evidence of an impact on these measures for pupils in schools that received Changing Mindsets. A positive impact was found for the intrinsic value measure, but the impact was small and was not statistically significant.

- Among pupils eligible for free school meals (‘FSM pupils’), those in schools that received the intervention did not make any additional progress in literacy nor numeracy—as measured by the national Key Stage 2 tests in reading, GPS, and maths—compared to FSM pupils in schools that did not receive the intervention.

- One explanation for the absence of a measurable impact on pupil attainment is the widespread use of the growth mindset theory. Most teachers in the comparison schools (that did not receive the intervention) were familiar with this, and over a third reported that they had attended training days based on the growth mindset approach.

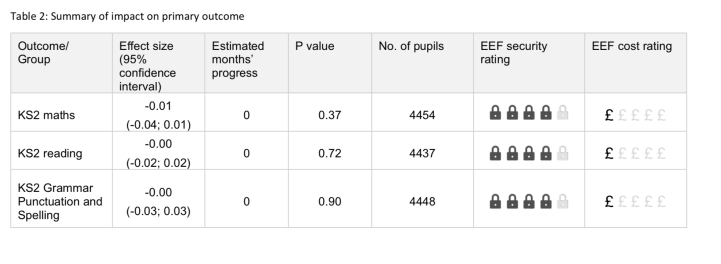

Using the EEF’s rating the system, the study produces the following outcomes:

Cheap, reliable data – and zero months’ progress! Essentially, the outcomes from the study were weak; disappointing for sure. The report suggests some contextual and methodological reasons why this might have been the case. This is important because it would be a big mistake to dismiss potentially good ideas based on flaws in a particular trial. Three possible issues are suggested:

In theory, there are three possible reasons why the intervention’s measured impact was not statistically significant:

- the programme was not delivered as intended, or was too short, so that pupils did not take on its messages and change their attitudes, behaviours, and, consequently, their performance;

- control schools were also using growth mindset approaches, and the treatment schools had already been using it to some extent; and

- the pupils were too young and that older children are much better able to use growth mindsets to improve their performance, particularly as reflected in tests.

Each of these factors is discussed in more detail in the report. My interpretation from reading it is simply this: implementing growth mindset interventions, even in controlled conditions with willing and committed schools, is HARD! Even accepting that growth mindset is sound as a concept, I would suggest that there is a long road to walk between altering the attitudes children have to their learning and securing improvement in their application of successful strategies to the learning itself. It’s never going to be a major effect because the potential for dilution and diffusion of effort and thinking time away from activities critical to the actual learning is significant.

The Metacognition Report, by comparison, suggests a much stronger outcome in EEF’s terms. The guidance report is not based on one specific trial – an important point – but a summary of multiple studies. However, the EEF Toolkit gives metacognition an impact rating of +7, with four locks for validity and very low cost; just one £.

Even if we take these ratings as a very approximate guide, there is a clear difference here. Metacognition and self-regulation strategies are cheap with a strong evidence base yielding a much stronger impact than the mindset intervention. This makes total sense to me . The guidance report details the processes needed for successful delivery of interventions, showing how it moves from teacher guidance and modelling to students using task planning and self-monitoring strategies independently:

All of this is located in subject-specific content. It’s not generic at any stage. Metacognition is something you model while teaching maths, science, English, art or French. You don’t waffle on about it in assemblies; you don’t turn it into laminated poster. It goes to the heart of the learning process and, therefore, yields results in terms of impact. It links to the ‘process questions’ that Rosenshine talks about in his principles of instruction – whereby teachers explore the ‘how do we know?’of the question in hand, narrating their thinking and exploring students’ thought processes.

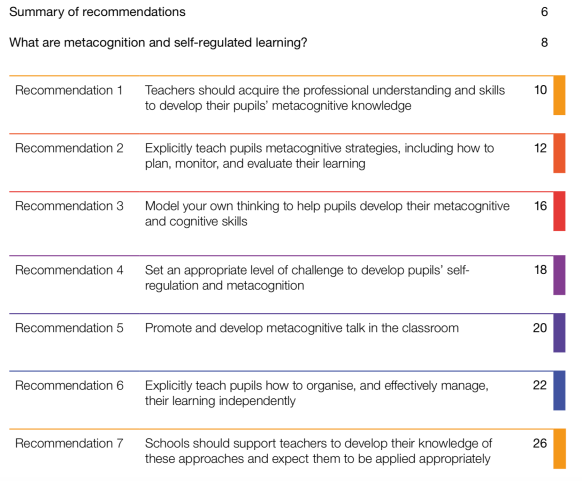

The report also gives seven recommendations for developing this approach in schools:

Conclusion:

I fully accept that the concept of a growth mindset is real and helpful. It would be great if teachers and students all had a growth mindset. The question is: how do we develop growth mindsets? I would suggest that the best bet for this is to focus on engineering success through applying the EEF’s recommendations, flooding lessons with metacognitive talk and lots of modelling. I would suggest that teaching students about mindsets forms a light-touch background at most – it’s obviously healthy to encourage students to persevere, to take risks, learn from mistakes and not give up. But – it’s far better to be a growth mindset school than to say you’re a growth mindset school and subject-specific metacognitive strategies are much more likely to foster the mindsets we’re after.

If evidence-informed practice means making decisions about where to spend the CPD time budget based on evidence, I’d say it’s pretty obvious that metacognition is by far the better bet.

Responding to ‘Mindsets vs Metacognition. Two EEF reports and a clear conclusion.’

Thank you very much for this Tom. You have given very clear summary of the research findings. There are just a few comments that I would add.

1. I understand entirely that in pure numerical terms it is perfectly valid to compare the impact of metacognition interventions with mindset interventions. A danger, unintended consequences we like to say these days, is that this can create an impression that it is either one or the other that the school should pay attention to.

2. You have stated that you believe that the ‘concept of a growth mindset is something real and helpful’. The challenge is that even though there has been so much discussion about a growth mindset there is still a lack of clarity about exactly what this means. Therefore when there are headline statements about the effectiveness or otherwise of adopting interventions around the mindsets of individuals in schools (both the students and the adults) the question must be asked about what exactly each of us is talking about. What exactly, for example, is your ‘concept’ of a growth mindset, how does it match with mine, and how does this match with the mindset of whoever is reading this right now?

3. You also state that ‘implementing growth mindset interventions, even in controlled conditions with willing and committed schools, is HARD!’ Yes it most definitely can be. And in my experience the most important factor in the level of success of the intervention in the school is determined by the headteacher or principal. Some leaders want to bring about a quick change through work on mindsets because they have heard from somebody else or read a brief article that gives them a belief that this could be good for the school. But deep down, if they do not have, at the very least, an open mind about the potential importance of what they are doing then they will tend to, understandably, refocus their efforts on other apparently more tangible, ‘low-hanging fruit’ interventions. On the other hand, other leaders are willing to embrace the potential for change which involves a journey into the complex nature of hidden beliefs, values, expectations, and habits that lie deep within each of us as well as within the school identity itself. Of course this is not easy, and it is why many schools will not commit to it. They may have wonderful displays about growth mindsets on their classroom walls (I have seen many of these) and they may say the usual things that are spoken about in terms of growth mindsets, but deep down within them (once again, them being individuals within a school and the whole school itself) they may be giving out subconscious signals which completely contradict their stated beliefs.

4. Ultimately, for me at least, the growth mindset approach of maintaining a belief in the inherent potential of each individual, and not putting them in a variety of different sized jam-jars in which they are then ‘allowed to operate’, is a significant part of developing a constructive culture within classrooms and whole schools. Changing the culture can take effort, determination, resilience, and grit (absolutely, a number of the things that are part of the discussion about what growth and fixed mindsets are all about). It is difficult but not impossible. And it is incredibly important to do. Kotter and Heskett in their longitudinal research provided evidence of the impact that a culture can have on the long-term bottom-line (profit if you like) for many businesses and you only need to extrapolate those results into a school setting to appreciate the importance of the culture of a school and its ‘business’ of providing high quality education as well as empowering young people with a belief in their own efficacy as they go forward in their lives.

5. Relative cost implication attached to work on metacognition and growth mindsets are to say the least rather nebulous. Of course we can provide a figure for any training that might take place, but the real effect comes from the implementation. And if adults in a school have not embraced the key principles from training about growth mindsets then nothing will change. Because this is about what is going on in their minds, and this is harder to determine than actions around metacognition that we can more clearly and visibly see within a classroom. Developing a growth mindset approach in the school is not about having an almighty splash (‘ we are launching growth mindsets this year and have a day of training on it in September’ – and that’s it), but instead it comprises the constant drip feed that goes on in classrooms, corridors and staff rooms in schools every day. The cost of each drip is very small, but the impact, like growing stalagmites and stalactites, can be enormous and spectacular.

Finally I believe that metacognition and growth mindsets approaches are both wonderful ‘children’ that have immense potential for bringing about the kind of healthy change and development that we are looking for in our schools. Both of them need to be understood, nurtured and supported if they are going to be sustainable and effective. Neglecting one of these children for the sake of the other would not be wise. We wouldn’t do this with children in our classrooms ………………… would we?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on From experience to meaning….

LikeLike

Nice post. I, too, hope teachers have a growth mindset. But a growth mindset develops beyond the classroom and this is doubly difficult when the teachers do not see why he needs it outside the classroom. Schools should ensure the teachers’ off-campus life exudes one with a growth mindset.

LikeLike

[…] Mindsets vs Metacognition. Two EEF reports and a clear conclusion. At ResearchEd in Cape Town I presented a workshop exploring two relatively recent reports from the Education Endowment Foundation – the 2018 guidance report Metacognition and Self-regulated Learning, and the 2019 report Changing Mindsets: Effectiveness Trial. Essentially, my argument is that these papers support the view – one that makes sense to me – that schools are better off investing time and energy in adopting strategies that develop metacognition than those focused on growth mindset interventions. […]

LikeLike

[…] Mindsets vs Metacognition – Tom Sherrington […]

LikeLike

[…] Should you focus on metacognition rather than mindset? […]

LikeLike