In my opinion the practicalities – the mechanics, the routines – of running a room so that every single individual in it is learning, are not sufficiently examined and spelt out in our training and professional discourse. If that were not true, then we’d see far fewer instances of lessons where multiple students are not fully engaged in the learning process and do not succeed, even when many other students do. In fact, it’s all too common. It’s also pretty challenging to get right – so any assertion that this is what most teachers do anyway or that it’s somehow patronising to discuss, is totally misplaced in my view. Actually, it’s because we don’t discuss it enough that so many lessons are run without the ‘all’ in ‘all students’ being explicitly, intentionally planned for.

I explored some of the challenges in my post about our thinking being upside down…

Teaching is fundamentally upside-down. Ensuring *everyone* succeeds should be the foundation – but it’s not!

Something I’ve reflected on a lot recently is just how widespread and deeply embedded certain problematic teacher…

Here I want to focus on solutions. However, I’m conscious that this intro could be for a whole book, not a simple blog post, so I’m only going to be giving headlines. The idea of choreography is to emphasise the intentionality needed to teach 30 children at the same time and the need to orchestrate what students do very very deliberately. Everything you do – everything – has to be reviewed with a key question in mind:

How will I make sure EVERYONE is learning?

This links to another previous post where I simplified this to three checks: Thinking, making meaning, practising.

Three Checks: For teachers and observers.

As I explored in a previous blog post, it can be useful to condense the complexity of teaching down to just a few…

A key factor in this is the need to check, not just assume. Children do not learn simply by being in a room where other people are learning. They each need to be active participants and, if we want to ensure learning is happening, we need to check that it is – for everyone: check they’re all focusing their attention and thinking; check they’re all making sense of things; check they are all consolidating through practice.

In practice this means combining a range of techniques across a lesson and each series of lessons weaving together four main modes of engagement:

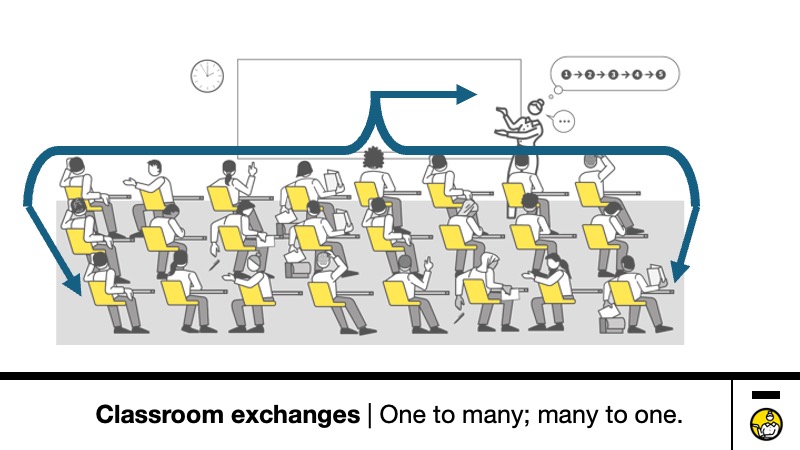

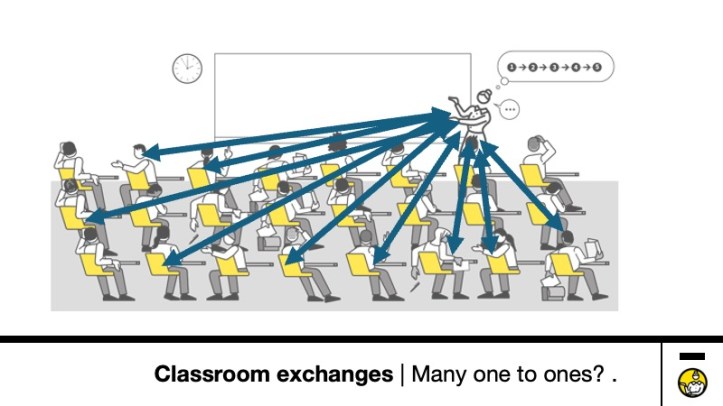

- Teacher engaging with the whole class – with limits on how interactive this can be.

- Teacher engaging with individuals – with limits on how many students can be involved except in specific instances like with Show-Me Boards.

- Students engaging with each other (in the image below -some are missing on this but in theory should involve them all!)

- Students doing things on their own. Ultimately this is what has to happen in each student’s head – but we need to know how that’s going.

At some point you need to use all four modes to sustain fully inclusive whole class teaching, establishing key routines and switching modes responsively. The question is when and for what purpose.

Attention:

The key is to engineer full attention intentionally, not assume it. It’s natural and inevitable that students – with their pesky human brains – will mind-wonder unless they have a strong pull to concentrate their focus on the material in hand. This has multiple elements:

- Teacher scanning, making eye contact, explicitly talking to all students into the corners of the space

- Accountability and expectations around responding: the norm is that students are ready to share their thoughts at any time; cold calling is totally standard, a warm invitation to respond – at any time. No volunteers, hands up, calling out, dominant students or students opting out.

- Framing questions so that they are explicitly aimed at everyone:

“Alright everyone, have a think: what is the trend shown in the graph… decent pause for thinking………. OK, Abdi, what were you thinking? ”

- Supporting all students to think by making sure they have resources to think with eg a table of information, worked examples, a pair of contrasting examples of work to compare – so that they are not just guessing.

- Directing attention to key parts of the material; explaining in small steps, managing cognitive load, using visual aids.

- Setting tasks that involve all students so they all have to show they are following because they have to do the task by themselves.

Prior Knowledge:

It’s a huge variable across a class and one of the hardest things to deal with – it’s much harder sustaining whole-class teaching when the baseline is very wide. However, it’s virtually impossible if you don’t know what the baseline is. Teaching has to be informed by assessment information but beyond that, day to day, some routines are helpful:

- Build on common concrete experiences:

- don’t assume they’ve all seen ice melt or noticed condensation: give everyone a cube of ice to hold and let them all create a cold glass of water so condensation forms on their own glass so they can all feel it, touch it and think about what’s happening.

- show a video that everyone watches;

- Set the context with a big picture overview:

- Don’t make risky assumptions – go back and set the scene: where are we in the topic? Where does the topic sit in a wider frame of ideas? Why is this an important area to explore?

- Run overview lessons as routine that allow subsequent learning to have a framing that supports schema-building. Eg Merapi is a volcano; just one of many; it’s just one example but it highlights the issues. Volcanoes are one of many events we call ‘hazards’ including earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis. Each one has Economic, Social and Environmental impacts. Merapi is on the island of Java, part of Indonesia – in SE Asia (looking at maps) and here’s the ‘ring of fire’. Etc .

- Check understanding of key words and concepts– question your assumptions

- Eg In ‘Why did Henry break from Rome?’ – what does ‘Rome’ refer to? When did this happen? What else was happening? Where in the world are we when we explore this story? Spell it all out.

- Why might teenagers move from recreational to dependent drug use? Check: what do ‘recreational’ and ‘dependent’ mean?

- Alveolus. Trachea. Hydraulic. Simile. Coordinating conjunction. Pathetic Fallacy. Engage all students in choral rehearsal of new vocabulary and phrases so that every student has said all the word and can explain their meaning, giving examples.

- Provide resources that enable students to fill in the gaps themselves (see agency below) A rule of thumb: imagine a conscientious student missed a few lessons due a medical issue. Think about what you would give them to catch up and then assume other students need this too; despite being physically present they didn’t follow. What does this look like? A good modern but old-fashioned textbook? (Yes!) Or something you’ve curated yourself? Whatever it is – you need it if you want students to develop agency in their learning.

Generative Tasks for Making Meaning :

You can’t see immediately whether students have made sense of the teaching – and you shouldn’t assume. But crucially, in seeking to find out, what is often overlooked, is that students don’t immediately know if they’ve made sense of things either. Students need some kind of generative activity that allows them to explore their own understanding.

Do I understand this? Let me find out!

Routines that support this include:

- Think Pair Share: posing a question that explores understanding or simple recall of what’s been said; inviting students to think, then share in turns what their sense of things is.. with the usual cold call accountability so that all pairs engage and prepare to share with the class. The simple idea of ‘talking things through’ is very helpful. Adults need this in their learning; children need it too. You don’t have time to hear each student tell you their version – but you can make sure they all tell their version to their talk partner and then check for accuracy.

- Practise explaining: a precise routine that involves all students – in turns, in pairs – in rehearsing the explanation that the teacher has given or that’s embedded in the reading, with tons of scaffolding to secure a high success rate. If they can explain it, they’ve understood it. (They may not yet have done enough to have built secure long-term memory but this shows if they make sense of it fresh from the explanation.) The teacher samples examples to identify gaps and misconceptions. It’s amazing how well this throws out early gaps in understanding.

- Individual question/task/activity: Very obviously, involving every individual student in doing task like attempting a maths problem, constructing a sentence or doing a basketball throw – just like the one the teacher did – will reveal a student’s understanding. Primarily to themselves. Can I do it? How well can I do it?

To summarise – all students need to engage in a generative task for themself to allow them to make sense of an idea and evaluate the extent of their success.

(See Shimamura’s MARGE: Generate; Evaluate). Sampling students to do this is far too common – and kind of ridiculous! Imagine a PE teacher teaching tennis backhand to a class but only asking two students to show them if they could do the backhand after seeing it modelled? Obviously, every single student needs to do this.

Checking for understanding

Alongside all students checking and making meaning for themselves – teachers need to check understanding across a whole class so that they are in touch with how things are going in real time. The purpose here to inform next steps of teaching as well as to make students think. To make this work with 30 children, you need a range of approaches in combination. This might include:

- Eliminate false checks: You have to stop relying on the useless rhetorical checks of the form: Did that make sense? Does everyone get that yeah? Are we all ready to move on? Teachers always laugh at the preposterous nature of these ‘checks’ – and yet they are so so so common. Recognising the delusion of it is the first step.

- Sampling by cold calling or show calling: You can find out a lot by sampling – provided that every student is a potential candidate and it’s the norm. If you hear three answers to a question or sample three student paragraphs, you normally have plenty of material to inform a decision about possible areas to reteach. But it’s only a sample…

- Circulating to check: the obvious thing to do as students produce answers or demonstrate a practical skill is to circulate actively to see how it’s going. Teaching is a high step-count profession, not one for sitting down. You need to get out between the desks and see how it’s going. This is often more important and useful than kneeling to support an individual. The more precise the task, the easier this is to do – looking for specific learning outcomes and spotting errors and deviations (which can be good or bad).

- Whole Class checks: Sometimes the most obvious thing to do is to check everyone’s answers/responses at the same time:

- Show-Me Boards: 3-2-1 and show me! This works because every student has to think for themself and show the teacher their answer – and thinking. Linked to cold calling, students have to ready to explain their thinking as the teacher probes to explore the range of answers, right and wrong. It should be a staple in most subjects where answers need to be aired to be known.

- Visible practice: In some subjects (PE, art, drama) – there’s the opportunity to see responses: you see the still life emerge; you see the tennis strokes as you look along the lines either side of the nets. You don’t need to take Show Me Boards out on the pitch!! The learning is already being made visible. The challenge is to set activities up so that you can check in on every student as they explore the skills.

An important component to emphasis here is that you need to respond to what you see. If students are all succeeding, consolidate or move on. If you spot errors or misunderstandings – address them. Now is the best time to do it. It pays to anticipate this with some idea of what you would need to have to hand if you find students are struggling.

An element of the choreography concept is that in order to succeed, teachers need to plan routines for each of these elements matching the nature of the curriculum, such that they are systematic and engage all students all the time. In addition, using a dance metaphor rather than using ‘mechanics’, the idea is to be agile and responsive: teachers need to be able to adapt to what happens -changing tack if that is needed and not being surprised when there’s a need to start again or allow a bit of divergence.

The Dynamics of Questioning….agile, responsive, nimble, purposeful.

Increasingly I find that it’s important and useful to explore teaching techniques through the twin-tracks of a) defining specific techniques so they are…

Culture of Error:

A massively important requirement for all this to work well is that you need to normalise the process of flushing out error. Instead of looking for some correct answers or fully correct/excellent responses (did anyone get them all right? ) the explicit goal is to find out who got things wrong and to explore what the underlying issues are.

So, for example, if you set 5 quick quiz questions, you do not want to get one correct answer for each question from someone in the room (such as a common but weak approach!) Instead, you give the answers to all questions and then you might routinely ask ‘who got four out of five?’ These students always tell you happily which one they got wrong. Once 2-3 students have volunteered their wrong answers, others freely follow suit. Generally, teachers need to normalise seeking out problems, challenges, concerns, questions, uncertainties. Instead of asking for ‘any questions’, set a short task: ‘In your pairs discuss which parts of this concept you think are the hardest to grasp and be ready to share’.

Feedback:

Students need to know how well they are doing. This has many elements:

Is it right or wrong? Is it good enough? Is it excellent? Can I do it on my own? What is missing? Again, a key challenging in scaling up from one to 30 is that you can’t realistically give individual feedback mid-lesson. Here we need to harness the Wiliam et al Formative Assessment strategies amongst others.

- Self-Assessment: (learners as owners of their own learning). Students need to learn routines for self-checking: using simple factual answers to questions to compare to their own; using model answers and exemplars for more extended pieces; applying success criteria for tasks to their own work: ‘things you can tick’! ie – are these elements present in your work? Quality criteria are harder to apply but it helps to explore: is your response as ‘persuasive’ as this exemplar?

- Whole class feedback: sometimes it’s very efficient and effective to give general feedback to the whole class, citing specific examples of success, common issues to address, bad mistakes. This then feeds into self-assessment as students evaluate which elements apply to their work. There’s a lot of thinking involved here -so there’s a good chance of most students learning a lot from the process. ‘Spot your mistakes’ is a powerful idea.

- Peer Assessment: (learners as resources for one another). Supported by good resources that provide definitive references for correct answers or quality work, students can evaluate each other’s work, most efficiently in pairs. Often a partner can see errors students do not see for themselves. In doing the assessment of their peer, they are also learning about the content and what success looks like for themselves.

The important thing here is that the ideas work in combination with each other and with the culture of error. No one process is enough alone – and there is still a need for teacher assessment of certain pieces of work and tests outside class time. The point is that, during lessons, teachers need to be close to what is happening and students need to have their knowledge gaps closed in real time as much as possible.

Responsive Verification Loops.

A common cycle in lessons that can have a low success rate is this:

- Teacher asks questions; sets a task.

- Students respond and reveal their understanding – including some errors.

- Teacher notes errors and responds, telling students the correct answer or re-explains.

- End.

The problem is that, for the weakest learners – those who got things wrong in the first place – this does not go very far towards closing the loop. All the assumptions made in the original teaching are still there: that the student will listen, make sense, self-correct and do better next time. The key is to find out if this is has worked via routine use of verification loops:

- Teacher asks questions; sets a task.

- Students respond and reveal their understanding – including some errors.

- Teacher notes errors and responds, telling students the correct answer or re-explains.

- Teacher repeats or reworks task or questions to explore whether this worked

- Students respond again, hopefully showing improved understanding.

- Teacher evaluates and decides whether to move on, reteach again or defer, (taking account of effort, attention etc).

- End.

Of course, this takes some time – but it is time invested, not time wasted. The payoff is deeper understanding of more students. And, in principle, those weakest students need the most help; if lessons are meant to be inclusive, it’s not an option just to leave them behind.

Guided and independent practice:

Possibly the thing I get most questions about – because it’s the hardest thing to do – is to manage the situation when some students are succeeding and others are not. It seems impossible to support the lower end and continue to stretch the top end of the range all at once. No question – these needs thought and planning. I would say there are three general principles to establish and work on lesson to lesson.

- Scaffold for high success rate:

The principle is that students need to experience success with whatever help is needed to achieve that, before supports are removed and students then see if they can be successful on their own. Planning scaffolds is essential, subject by subject, task by task. For example:

- involve all students in practising explaining a process using fully labelled diagrams before seeing if they can do it with unlabelled diagrams or can create their own diagrams.

- use extended guided practice of a writing task, seeking to emulate a clear exemplar, before students try things independently and creatively.

My favourite recent book on this is The Scaffolding Effect by Rachel Ball and Alex Fairlamb – it’s full of practical ideas and examples. Of course, scaffolds are meant to be temporary and the moment of taking them away should be known and explicit. Now let’s see if you can do it by yourself….

- Establish a ladder of difficulty with progressive pathways:

Without getting into the whole debate out ‘differentiation’ – a ladder of difficulty is inherent in all learning processes whether we like it or not. The key is to be intentional and flexible in moving up the ladder. Managing this type of divergence whilst keeping people reasonably close requires careful monitoring – circulating during guided practice – but it’s necessary. You don’t want half students struggling or half waiting around… you need practice tasks for everyone to do at a level that balances challenge with confidence-building.

Examples might be:

- tiered question sets in maths or science. Set A prepares for Set B which then builds towards Set C etc. Students might progress at different rates; some might skip directly to the next set along because they can!

- threshold tasks: everyone has to complete Task A to show they’ve achieved key learning goals before moving into a more flexible independent practice mode. E.g drafting a high quality first paragraph with repeated edits and redrafts as needed, before moving onto complete a fully extended piece.

Everyone should know what to do next. Nobody is ‘finished’, waiting about but they need to check in to make sure their foundation task is good enough.

- Foster agency and develop self-assessment routines

This idea is actually an important learning goal in itself if we’re looking to develop students as independent learners able to pursue learning away from the classroom, not least when they’re preparing for important assessments or exams. However, it is also a helpful idea in the context of teaching 30 students all at once. It is very helpful, if not totally necessary, that you devolve some of the assessment and feedback work to students themselves – as many as you can. This starts with how we process responses in questions and tasks:

Did you get it right? Does your work meet the criteria? How could you improve your performance.

Beyond that agency builds into students being able to read for learning with increasing independence. This ‘five ways’ post signals the way:

Five Ways To: Foster Student Agency

It’s common to come across situations where the idea of independent learning is being promoted. However, this can be quite…

With these things in place, you create a learning space and timeframe that extends beyond the classroom and you can use it to design extended practice and consolidation tasks or more open-ended learning appropriate to what learners need across the class.

Conclusion.

I knew this would be a long one! I would say that both of these things are true:

- All of these ideas can be implemented and often are; when done well, you get truly inclusive classrooms. It is definitely possible to teach 30 children all at the same time and, though never easy, many teachers succeed.

- Because it’s not easy and has not been an embedded focus in training, it is still not the default mode of teaching for a lot of teachers where the ‘all’ often seems out of reach, too time consuming or unrealistic in one way or another.

I’ve expressed this issue in multiple ways before and it always comes down to making this a focus on CPD, one step at a time. Like many things, it begins with acknowledging the issues and seeing the possibility of change. With a stronger understanding of the possibilities in classroom choreography and sustained intentional practice, things can improve significantly.