Recently I’ve been asked to deliver PD sessions about oracy and, separately, about ‘stretch and challenge. I’ve also been asked to share ideas about developing independent learning./fostering student agency and what I’ve termed ‘Mode B’ teaching – which encompasses all of these things, including projects and enquiry work.

Where people are keen to explore this territory, I’ve often found that they are a bit lost knowing how to translate their good intentions into concrete actions. It doesn’t help when commentary from champions of these things emphasises nebulous ideas like needing ‘a culture of oracy’ or when they appear to disparage specific concrete ideas with statements like ‘oh gosh, there’s just SO much more to oracy than giving a speech or doing think pair share’.

On the other side of the fence, I also find it confronting when people are totally dismissive of the ideas –

- oracy: too vague and undefined. It’s not even a thing.

- projects- nope, they disadvantage disadvantaged children; opportunity cost.

- developing agency: nope – all that ‘flipped learning’ is just brain gym etc etc.

My response is this: Are you saying poor children can’t ever do a project? Isn’t that a bit patronising? Are you saying children should never make a choice about what they learn or the mode of response? Are you saying your students can’t be expected to read something and then share what they learned from the reading? Are you saying you don’t want all your students to develop confidence speaking and expressing their ideas?

The challengers nearly always cave – no, of course not; that’s not what I meant! But the thing is, you can’t have it both ways: if you want students to, at some point, share their ideas verbally, do a project or give a presentation or read independently or make a choice about what to study – that needs to find a home in the curriculum somewhere. It needs to be planned. You can’t just keep saying no. You need to embrace the idea and find a place for it.

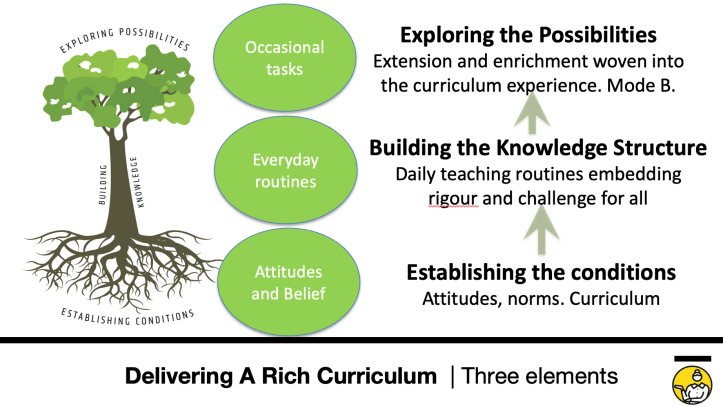

My solution to this pretty simple: I tend to apply the same three-part approach, whatever the issue at hand – and this seems to help make things seem meaningful and doable. It’s a blend of principle and pragmatism and links broadly to my learning rainforest analogy of tree-growth.

Very simply, when thinking about these ideas, it pays to consider:

- the attitudes and beliefs you need to foster before anything can happen.

- the things you can do routinely – every lesson or every week – that drive things forward, embedding the idea into the fabric of learning day to day.

- the things you might only do occasionally, even just once a year, but that still represent important elements of a student’s curriculum experience overall.

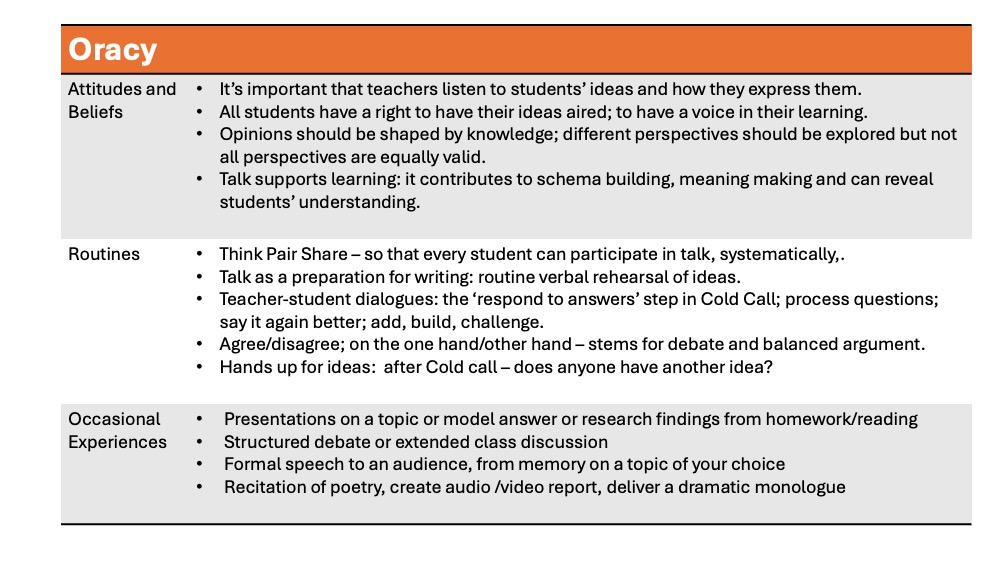

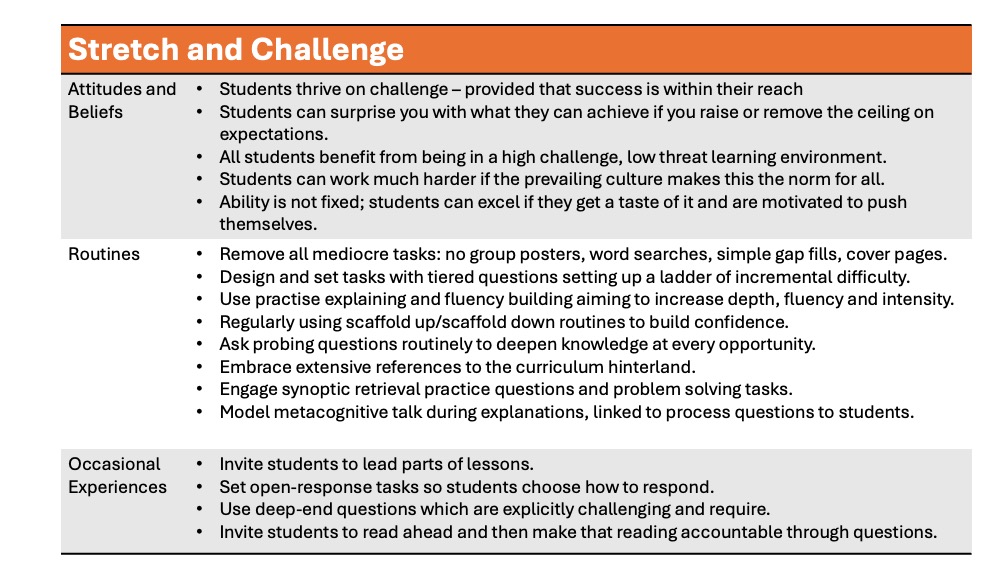

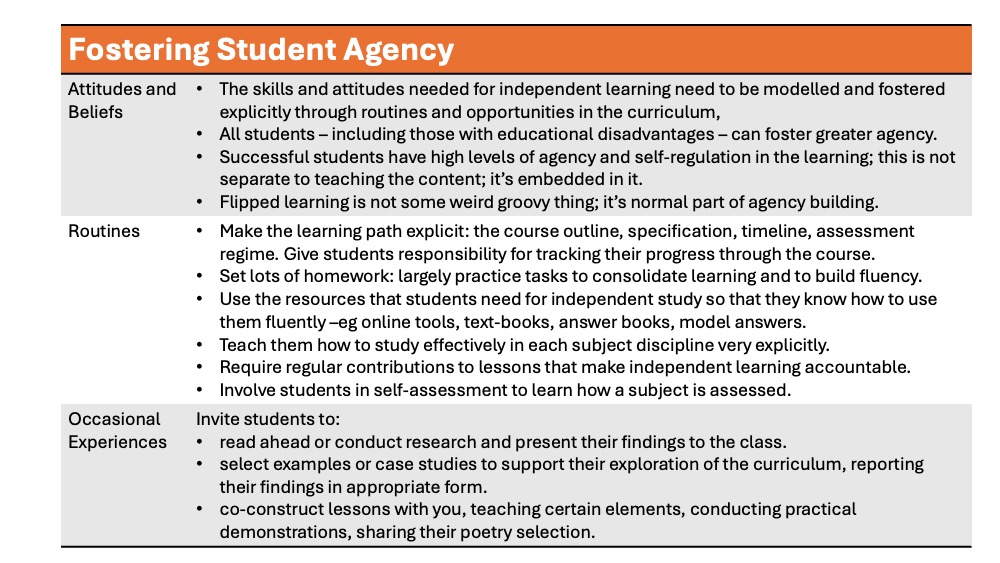

It’s important to explore your attitudes and beliefs from the start; if you don’t think it matters whether all students’ ideas should be explored verbally or that students respond well to reading challenging texts – you’re just not going to engage with it. If you or colleagues think a word search or a group poster with bubble writing are meaningful educational activities, it’s probably necessary to tackle that mindset before you worry about going further with ‘stretch and challenge’. . If the habit is to accept short shallow answers to questions in class, it’s going to be useful to examine why that might constitute low expectations rather than high expectations.

Of course, attitudes themselves don’t do the doing. It’s important to have practical classroom routines you use all the time so that students’ daily diet of learning has challenge, oracy, agency-building built in; this is how habits form and how cultures are shaped. It’s the day to day experience of learning that makes the most difference – the tangible activities students engage in, not the gushy, lofty position statement.

Beyond the routines, there are many occasional set-piece structures that deliver deep learning experiences for those involved. If you’ve taken part in a debate or produced a project on an enquiry question or given a presentation on poem you read at home – you’ll learn a great deal and these experiences don’t need to feature very often to have impact.

Here are some examples:

Oracy

Stretch and Challenge

Fostering Student Agency

With this framework, all the nebulousness of each idea turns into practical activities and routines you can plan, fuelled by the requisite attitudes and beliefs. Culture is no more than the sum of things that happen – and you can plan things that happen. There’s no need to talk in terms of ‘enquiry-based learning’ or ‘project-based learning’. You just set up an occasional enquiry or occasional well-structured project.

Oracy is comprised of daily routines of classroom practice and a set of experiences that happen over time – there’s no need to scoff that’s it not one or the other or to put people off by putting it on a doe-eyed pedestal of grand thinking that seems like a ton of work and faff that interrupts the flow of instructional teaching.

I hope this helps! It helps me so I hope it helps you.

I’m writing my Product Design unit planner for next year. All of this can be implemented into my workshop. Thank you for these insights!

LikeLike

[…] Tom Sherrington talks about how he uses his three element approach (Attitudes and Beliefs, Everyday Routines and Occasional Tasks) to making thi… […]

LikeLike