Recently my total preoccupation has been with the requirements of inclusive teaching – ie teaching so that every single individual student is thinking, making meaning, practising: learning! Based on what I typically observe in lessons in my current line of work, it seems that the biggest challenge is rarely that the work is too easy – it’s that the lowest attaining students are left to struggle too much or are just left out; left behind.

But – having just re-read some of my old posts I realise that I was also once strongly preoccupied with the need to ensure that all students are challenged. I’ve previously said that too many children are systematically under-challenged. But can this also be true? And, if so, what should teachers do about it? On the face of it, my emphasis has shifted but if you read both of these blog posts – I think they both still apply. Ideally we shouldn’t have to pit these ideas against each other…… but is that realistic in practice?

Teaching to the Top: Attitudes and strategies for delivering real challenge.

Teaching to top has been a long-standing principle of effective teaching from my perspective. One of my early blogs was ‘Gifted and Talented Provision:…

Teaching is fundamentally upside-down. Ensuring *everyone* succeeds should be the foundation – but it’s not!

Something I’ve reflected on a lot recently is just how widespread and deeply embedded certain problematic teacher behaviours are and just how unnatural the…

The holy grail is to teach in such a way that every learner can make strong progress. This requires a curriculum context that is inherently challenging and attitudes and techniques that ensure that nobody held is back and nobody is left behind. But do you teach to the top band of students as the main driver of your lesson design but then do you best to support people in the lower band with some scaffolds? Or, do you base your lessons around ensuring the low band students are building confidence, going back as far as necessary to reconnect with what they know, and then offer as much challenge to the top band as you can manage alongside.?

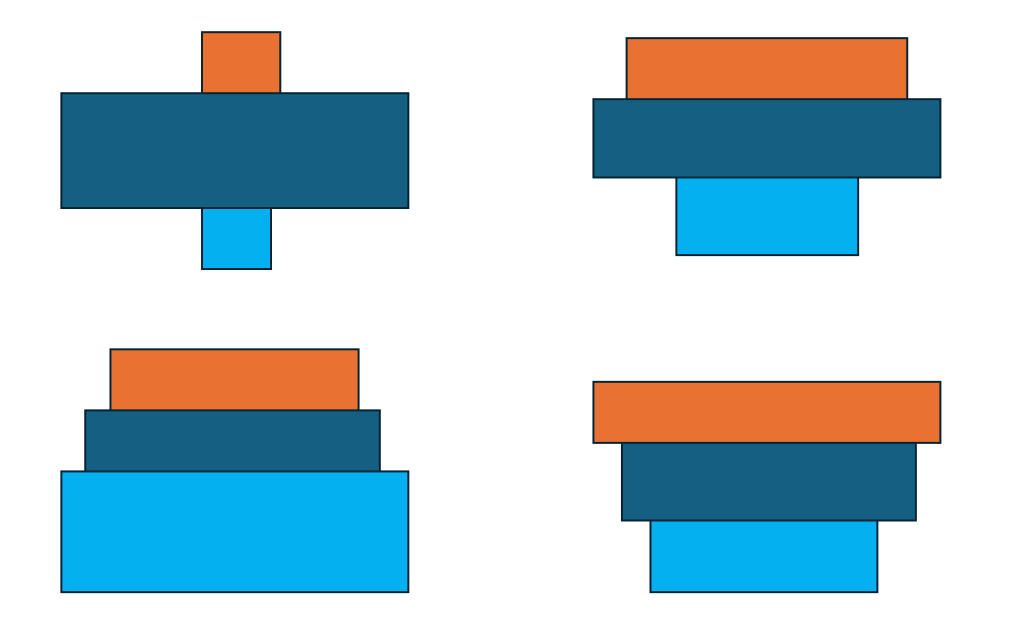

I often think deliberations on this are massively shaped by the profile of the classes people teach. Obviously every class is a mixed attaining class to some degree but the spread can vary significantly, Graphically, if we use three crude bands – low, middle and high – the profiles might look like this:

If you have a few outliers either side of the middle band you would have a different set of issues to someone with a large low band or high band. And obviously, you’re also simultaneously trying to avoid using these very crude labels or letting them become self-fulling indicators of outcomes. But reality bites.

The reason we have setting – most commonly in maths in secondary schools – is because the curriculum content can diverge for different bands and it becomes increasingly difficult – if not impossible – to teach everyone in the same class. Where some students are still wrestling with basic operations of even fractions, decimals and percentages, it’s hard to also teach solving quadratic equations. It always bugs me when crusading researchers highlight the injustices of setting.. you just want to say ‘come and these all these diverse students in one class and let me know how you get on!’.

So, what to do? Having spend many years teaching in fully comprehensive schools with a massive attainment range and mixed attaining classes, I find a number of metaphors have helped me with this. I’ll explore them all briefly:

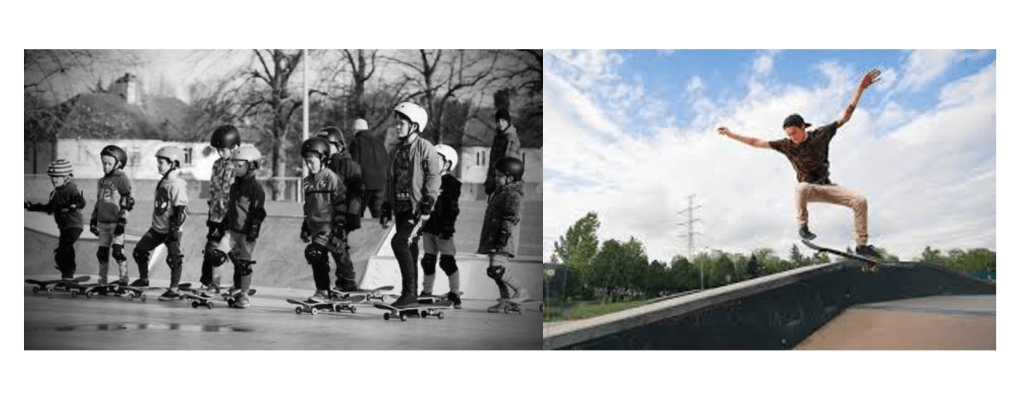

1. Skateboarding Lessons

The point here is to face the challenge head on. Imagine you have a class that contains absolute beginners and some self-taught skateboarding wizards and there’s only one skate park. What do you do? For sure, what you cannot do is teach them all exactly the same way and hope for the best. The wizards don’t want you to model the basics for fear you’ll hold them back. The beginners don’t want to be faced with the half pipe or rail and told to just give it a go! We’d have broken arms galore. (In reality most kids don’t go skateboarding; it seems difficult and intimidating to them.) The point here is that whilst trying to maintain a collective spirit with some whole class input, you have to have an approach to practice that allows them all to move forward and that can’t be the same for them all.

Another lesson from this that whilst skateboarding is inherently challenging, as a teacher you can inadvertently hold the high band students back if you reduce their agency as learners. If you are going to give a time to get the beginners going, you have to develop practice routines that the wizards can do by themselves. At the same time, when you give attention to the top band, you must be totally sure the beginners are able to practise safely. This means supports and safeguards must be in place for them all to manage the risk with appropriately designed practice routines.

The final point is that there’s a class contract at play. In placing those students together in one class everyone has to accept the deal: we’re all here to learn skateboarding – some of us currently can do it better than others, but everyone in the class matters as much as anyone else and we’re all aiming for excellence. We’re a collective working together; not merely individuals fighting for attention. That means, there has to be an acknowledgement from all parties of their role in that collective -to support each other, to tolerate imperfections and to accept that the teacher is human with limited capacity.

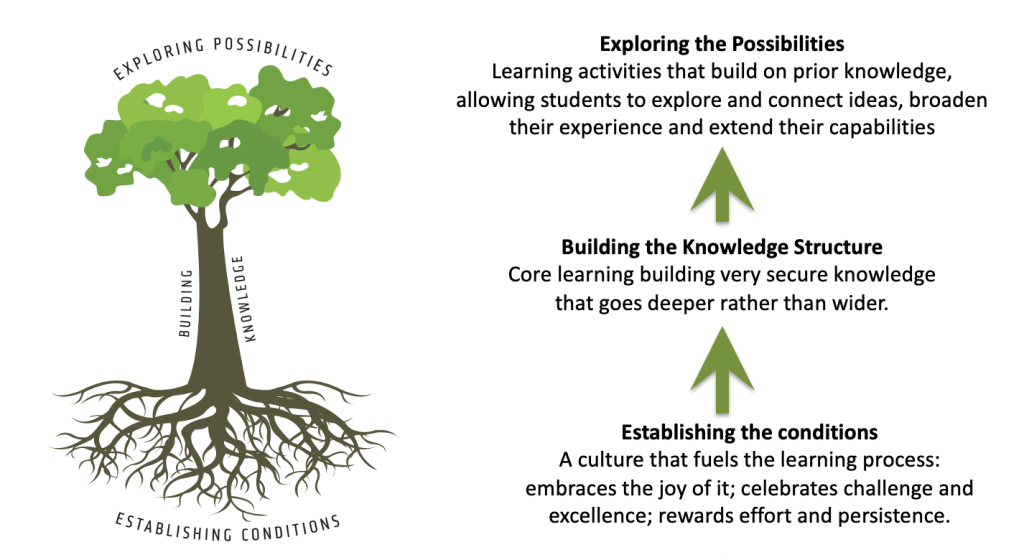

2. The Learning Rainforest Trees.

I’ve written a whole book about this but, to be brief, the metaphor builds on the idea of diverse growth patterns – embracing organic variety (there are many ways to demonstrate excellence) with a secure scientific understanding of how growth happens.

- The conditions in a classroom need to embrace both the challenge and the joy of learning and also the value of hard work. The curriculum has to be fundamentally challenging for the highest attainers – so that it is challenging for everyone. The risk of dumbing down, lowering expectation, when making a soft curriculum design choice is high for everyone. Ambitious curriculum thinking is important in an inclusive classroom. We’re all aiming to climb that big mountain ! At the same time, the baseline of ‘everyone matters as much as anyone else’ needs to be secure there too. It’s never sink or swim.

- In order to learn successfully, we need to build secure knowledge – everyone needs this, building new knowledge linked to a structure of connected ideas – the strong trunk and branches in the tree. I still believe that the concept of a ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’ is vital. Alongside that, strong instructional teaching is the cornerstone – fuelled by formative action and feedback.

- Finally, exploring the possibilities is the long term goal. Everyone should do some of this enriching, challenging ‘mode B’ stuff; some need support but the most sophisticated learners can do more, sooner, more independently. They have the knowledge and the agency to drive their own learning in many different directions. We have to build agency explicitly because ultimately our students are doing a lot of learning on their own, not least when revising for exams. This starts young and builds; you don’t just suddenly become an effective independent learner in Year 11.

3. ‘Differentiation as Gardening’

This analogy is part of the advice I give to newer teachers wrestling with this issue. We need to make this all doable – so the analogy is more pragmatic than principled – described in this post alongside many other ideas.

Dealing with Day-to-day Differentiation

This week I ran a session on differentiation with our NQTs. I felt it was a good, open session where we could all share some ideas and describe the challenges that we face in meeting the learning needs of all of our students. The fact is that we all find it hard – and that’s…

The key idea is that, as with gardening. you need to mix an approach that secures the core requirements for success for everyone in a blanket way but then give attention to individuals over time depending on their needs and success rate. So, strong inclusive teaching routines are essential day to day. But then, you also need to review progress from lesson to lesson, week to week, identifying which students need specific kinds of support to deal with learning challenges – from across the whole attainment range.

This doesn’t mean you can neglect students. High attaining students shouldn’t be waiting around for ages doing nothing; lower attaining students shouldn’t be left stuck, unable to move forward for long periods. But if the core practice tasks are varied enough, most people can get on with them while you move around supporting individuals. Some days you might to devote a chunk of time to a very small number because they’ve got a common learning issue to address that the others don’t have.

Another caveat here is that there are some students you can never simply neglect, hoping they’ll cope. For example, if you have a partially sighted student who cannot read unless the text is adapted for them – that’s not something you do whenever you get the chance. It has to be done systematically every lesson, come what may. You’re not doing them a favour; they are entitled to have materials they can access just like everyone else. Some things are absolutes.

4. Attitudes; Routines; Extras

Finally, I’ve found this framing helpful – as explored in detail in my Teaching to the Top post linked above. To plan for successful inclusive teaching that is also challenging for all, it helps to think about your approach in three areas:

1. Attitudes:

It’s a cliché but true: if you don’t think someone can do thing, you’re right. Explore the boundaries of what students are capable of – let them take some risks; the more challenging text; the more synoptic question; working more independently; trying without the scaffolds. If you project your own limitations onto students you hold them back.

At the same time, you need to embrace the flip I describe in my last post:

Teaching is fundamentally upside-down. Ensuring *everyone* succeeds should be the foundation – but it’s not!

Something I’ve reflected on a lot recently is just how widespread and deeply embedded certain problematic teacher behaviours are and just how…

Creating a culture of error is vital to making this work. Seeking out error is an attitude; a habit of mind for everyone. It means you don’t over praise correctness and ask ‘who got them all right’. Instead you focus on finding out who got things wrong; discuss errors, relative quality, misconceptions, forgetting. We’re all on a learning journey; sometimes it’s hard – but let’s let those who find it hardest come to the fore and build their confidence.

No-one held back; no-one left behind.

2. Routines

I could say ‘follow Rosenshine’s principles’ as a summary – and that wouldn’t be far wrong. Day to day, you need routines that blend inclusion with challenge:

- Routine knowledge checks, establishing prior knowledge gaps and then reteaching as needed.

- Plan and deliver explanations carefully building on prior knowledge, checking for understanding as you go along. Eliminate all those lazy habits – ‘does that make sense?’ etc!

- Emphasise rehearsal and consolidation with practice routines that involve everyone – thinking as individuals, not in groups where the weakest students’ issues are masked. Consolidation benefits everyone.

- Use the idea of a ladder of difficulty to prepare and deploy practice questions or tasks at varying levels of difficulty or with varying degrees of scaffolding so you can flex the practice you set across the class. Make sure you guide the practice with a high success rate before setting them off to practice independently. If they can’t do it yet with help, keep helping!

- Use the trio of inclusive questioning techniques absolutely routinely: Cold calling, show-me boards and Think Pair Share. Flex the depth of probing according the answers you get, building confidence and/or probing ever deeper.

The Dynamics of Questioning….agile, responsive, nimble, purposeful.

Increasingly I find that it’s important and useful to explore teaching techniques through the twin-tracks of a) defining specific techniques so they are…

3. Extras:

Finally, be ready to blend in occasional activities that add to the curriculum diet for everyone, offering some open-endedness, some choices, some agency with multiple ways to express understanding or produce excellent outcomes. This is the Mode B concept. It might include:

- Open-response tasks. Show your knowledge in multiple formats – (recognising that in the AI era this needs to be linked to real-time checks like tests and oral vivas.)

- Presentations and instructional inputs from students

- Collaborative tasks that support students to reinforce each other’s knowledge – such as elaborative interrogation, peer-supported retrieval

- Choices of content – such as ‘meanwhile elsewhere’ in History or selecting case study examples to report on – such as adaptations of organisms or interesting applications of materials in science or case studies of hazards in geography.

So, to conclude, yes I think teaching to the top and inclusive teaching are compatible. It comes down to strong curriculum design and secure inclusive routines, fuelled by a certain sense of drive, striving for excellence but always always being determined not to leave people behind. It’s hard but it’s the core of what makes teaching so rewarding. The key is to explore it all explicitly and face the challenges head on, never assuming it’s all sorted – because like a garden, it never is. It’s always dynamic – so you need to be responsive to greatest extent possible.