Classroom Voices is a series of guest posts providing a platform for teachers to share their ideas. All posts including all images are shared without comment or edits. To contribute, use this link:

Guest Author:Trent Stickland

Trent Stickland is Deputy Head Pastoral at a secondary school in North London: http://linkedin.com/in/trent-stickland-41791825

The Dark Room: A Night at Leeds Castle

It was late, and I was lying awake in the Butler’s Room at Leeds Castle. An elegant space steeped in history, its windows overlooking the grand entrance where, under Lady Baillie’s ownership, royalty, statesmen, and silver screen icons once arrived. The day had been filled with rich discussion, an education leaders’ retreat focused on the future of technology in schools. We had dined in the castle, wandered through its drawing rooms, and listened to stories that brought centuries of history to life.

And yet, as I lay there in the dark, I was confronted with something quietly unsettling: I couldn’t see any of it.

Not in my mind, at least.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t conjure an image of the butler himself, nor imagine the whispered conversations he might have overheard, or the scenes that unfolded in that very room. My thoughts were active, but my mind’s eye was blank. The room around me was dark, and so was the one within.

This inability to visualise didn’t begin at Leeds Castle—it had been quietly shaping my learning journey for years.

That feeling of absence, of something missing, took me back to a different room, many years earlier. An English lesson with Mr. Hoby. We were tasked with writing a piece of prose. I had an idea, something about a red squirrel being driven from its home by an invading grey. The concept was there, the conflict clear. But when it came to describing the scene, I froze. I couldn’t picture the forest, the squirrels, or the chase. My imagination had no canvas. My mind, again, was a dark room.

It wasn’t until quite recently that I discovered the name for this: Aphantasia. I have an inability to conjure mental images and with that I understood that I experienced the world differently to many of my peers. In that moment at Leeds Castle, I realised just how profoundly this invisible difference had shaped my own journey as a learner. And more importantly, how understanding is now essential to my perspective as a leader committed to accessibility and adaptive teaching for every student in our classrooms.

Defining Aphantasia: The Missing Picture

The catalyst for understanding my own experience arrived unexpectedly while reading John Higgs’ William Blake vs The World. Higgs, inspired by Blake’s descriptions of his own visions, an intensely vivid, almost hallucinatory mental imagery, explored the vast spectrum of human imagination. He noted that the very concept of imagination has historically been placed everywhere from the lowest rank of mental faculties by the philosopher Plato to the ‘queen of the faculties’ by the French poet Charles Baudelaire. Higgs highlighted how the experience of the “mind’s eye” is far from uniform, ranging from the intensely visual to the completely dark. Aphantasia is defined as the absence of a ‘mind’s eye’. Unlike the metaphorical understanding I had always held, Aphantasia means that while I can think about an apple, I cannot consciously picture it. I had presumed the mind’s eye was a metaphor, unaware that others genuinely possessed an inner screen.

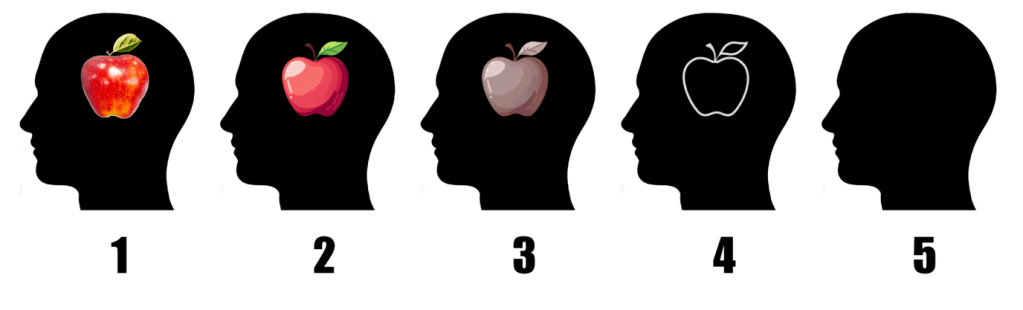

To illustrate this spectrum, imagine the widely used apple test: Close your eyes and try to conjure an image of a bright red apple.

A representation of how people with differing visualization abilities might picture an apple in their mind. The first image is bright and photographic, levels 2 through 4 show increasingly simpler and more faded images, and the last representing complete Aphantasia shows no image at all.

For most, an image either vague or detailed will appear. For those with Hyperphantasia (Blake’s world), the image is pin-sharp, accompanied by scent or texture. For the Aphantasic, there is nothing but darkness; the knowledge of the apple is present, but the visual experience is entirely absent.

Prevalence and Ignorance

Despite its profound effect on cognition, this phenomenon is surprisingly common yet relatively unknown. It is estimated that Aphantasia affects around 1% of the population, while approximately 3% experience Hyperphantasia. This means millions of people globally inhabit a completely non-visual internal world. Crucially, a considerable number of these individuals, like myself until recently, are entirely unaware that their internal experience differs so dramatically from their peers, leading to misunderstandings particularly in educational settings.

The term Aphantasia was only coined in 2015 by neurologist Professor Adam Zeman of the University of Exeter, deriving from the ancient Greek phantasia (‘appearance/image’) and the prefix a- (‘without’). While the phenomenon was first described by Francis Galton in 1880, modern scientific interest has only recently revitalised the study of this neglected aspect of human experience. Understanding this spectrum is the essential first step in ensuring our classrooms are truly accessible to all minds.

Personal Experience: The Aphantasic Artist and Educator

Given my lack of a mind’s eye, a curious irony emerges in my professional life: I am an educator of Photography with a First Class (Hons) BA and MA in Photography. My teaching spans Fine Art, Photography and Printmaking, fields often assumed to rely heavily on visual imagination. And yet, I am unable to conjure mental images.

Contrary to assumptions, Aphantasia does not limit creativity. My artistic practice thrives on external observation and conceptual depth, demonstrating that creativity is not confined to visual imagination.

This paradox is not a contradiction; it is a clue.

Aphantasia, far from being a deficit, has shaped a distinctive cognitive style in me. Because my mind does not generate internal images, I engage with the world through direct observation, analysis, and conceptual reasoning. My artistic practice is grounded not in imagined scenes, but in the tangible, external world. As a photographer, I do not “see” the image before I take it, I respond to structure, light, and form as they exist in real time. My work is driven by composition, pattern, and meaning, not mental pictures.

This is especially true in my specialism in the field: traditional photographic hand printing. The darkroom, now a literal space of controlled darkness, becomes a metaphor for the Aphantasic mind. In this environment, success depends not on visualisation but on precision: chemical timings, procedural accuracy, and tactile engagement. This empirical discipline rewards logic, method, and external feedback qualities that align seamlessly with the Aphantasic cognitive profile.

In the classroom and in leadership, this same profile manifests as a strength. I am a conceptual thinker, a “puzzle brain” drawn to systems, structures, and connections. I work best with analytical frameworks and logical sequencing. My thinking is scaffolded not by imagery, but by relationships between ideas. This has enhanced my capacity as a researcher and practitioner, allowing me to interrogate pedagogy, curriculum, and policy through a lens of clarity and coherence. These qualities have been a huge part of my journey as a leader.

These personal insights have not only shaped my understanding of Aphantasia but have also informed my approach to inclusive pedagogy.

For learners with Aphantasia, this cognitive style is not just a personal trait, it is a pedagogical imperative. It calls for adaptive teaching: approaches that do not assume visualisation as a default, and that offer alternative pathways to understanding. It challenges educators to rethink how we present information, assess creativity, and support diverse cognitive profiles in the classroom.

Adaptive Approaches: Conquering the Barriers

Traditional assessment methods often rely on visualisation, such as imagining scenarios or visualising processes. For Aphantasic learners, these methods can be exclusionary. Alternative assessments that focus on verbal reasoning, tactile engagement, and conceptual understanding offer more equitable measures of student learning.

For students with Aphantasia, and indeed for many others whose learning preferences lean away from visualisation then the traditional classroom can present invisible barriers. Tasks that rely on mental imagery, such as visualising a scene in a novel, mentally rehearsing a process, or imagining a scientific model, can become sources of frustration or exclusion. But these barriers are not fixed. They can be dismantled through thoughtful, inclusive design.

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework, developed by CAST, offers a powerful lens through which to address these challenges. UDL encourages educators to provide multiple means of representation, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of engagement, ensuring that learning is accessible and meaningful for all.

Here are some practical, adaptive strategies that align with UDL principles and support learners with Aphantasia, while benefiting the wider classroom community:

| Dual Coding | Use visual anchors with keywords by pairing photographs or diagrams with key terms to reinforce concepts.Present step-by-step visuals with accompanying verbal explanations to guide learners through processes or narratives.Encourage students to create their own visual representations of ideas, even if they rely on external references rather than internal visualisation. | Example: In photography, show visual examples of composition techniques alongside the terminology to build understanding. |

| Verbal and Conceptual Approaches | Use precise, descriptive language to scaffold understanding. Instead of asking students to “picture” a scene, describe it in structured, sensory terms.Encourage conceptual thinking by focusing on themes, relationships, and cause-effect dynamics rather than visual detail.Model verbal reasoning aloud, talk through your thought process when analysing a text, solving a problem, or planning a task. | Example: In English, instead of asking students to imagine a character’s appearance, prompt them to infer traits from dialogue, actions, and relationships. |

| Physical and Tactile Learning | Incorporate manipulatives, models, and real-world objects to externalise abstract concepts.Incorporate drama, engage in role-play, and encourage physical movement to explore narrative, sequence, or spatial relationships. Encourage sketching or building as a way to construct understanding, even if the learner cannot visualise internally, they can create externally. | Example: In science, use 3D models of molecules or the solar system to explore structure and scale without relying on mental imagery. |

| Systematic and Structural Tools | Emphasise logic, structure, and sequence through flowcharts, timelines, and graphic organisers.Break down tasks into steps and use checklists or procedural guides to support planning and execution.Highlight patterns and frameworks that help students make sense of content without needing to visualise it. | Example: In history, use cause-and-effect diagrams or thematic maps to explore complex events and their interconnections. |

| Technology as a Cognitive Extension | Leverage digital tools that externalise thinking, such as mind-mapping software, collaborative whiteboards, or audio note-taking apps.Use screen readers, text-to-speech, and captioning to support multimodal access to content.Offer alternatives to visualisation-based tasks, such as audio storytelling, coding simulations, or data analysis. | Example: In geography, instead of asking students to draw a mental map, use GIS tools or interactive maps to explore spatial relationships. |

These strategies are not just accommodations, they are enhancements. They reflect a shift from a one-size-fits-all model to a responsive, inclusive pedagogy that recognises the diversity of cognitive approaches in every classroom. For students with Aphantasia, they remove the pressure to “see” what cannot be seen. For all learners, they open up new ways to think, create, and connect.

The Wider Adaptive Teaching Imperative

Aphantasia is just one example, albeit a striking one of the many hidden, invisible conditions that shape how students experience learning. It reminds us that the internal worlds of our learners are not uniform. Some students see vivid mental pictures; others, like me, see nothing at all. And between these poles lies a rich spectrum of cognitive diversity that too often goes unrecognised in our classrooms.

This is the heart of the adaptive teaching imperative.

When we design lessons based on assumed internal experiences, such as the ability to visualise, we inadvertently exclude those whose minds work differently. Aphantasia challenges us to rethink what we mean by imagination, creativity, and understanding. It urges us to move beyond the visual and embrace structural, verbal, tactile, and conceptual approaches that make learning accessible to all.

But the principle extends far beyond Aphantasia. It applies to every learner whose cognitive profile diverges from the norm; those with dyslexia, ADHD, autism, or simply different ways of processing information. Adaptive teaching is not about lowering expectations; it is about widening the pathways to success.

As educators, we must commit to designing learning that honours this diversity. We must ask not just what we are teaching, but how we are enabling students to access, express, and engage with that knowledge. The Universal Design for Learning framework gives us the tools. The stories of students with Aphantasia give us the urgency.

Seeing Beyond Sight: A Call to Action

Aphantasia is more than a neurological curiosity, it is a profound reminder that the internal landscapes of our learners are as diverse as their external identities. In recognising this, we are called to reimagine what it means to teach inclusively. Adaptive teaching is not a concession; it is a commitment to equity. It is the belief that every student, regardless of how they visualise, process, or express ideas, deserves access to meaningful learning.

By embracing frameworks like Universal Design for Learning, we move beyond assumptions and toward intentional design where lessons are not built for the average learner, but for the full spectrum of minds in our care. Aphantasia challenges us to expand our definitions of creativity, imagination, and understanding. But more importantly, it invites us to lead with empathy, to teach with flexibility, and to build classrooms where every learner, seen or unseen, can thrive.